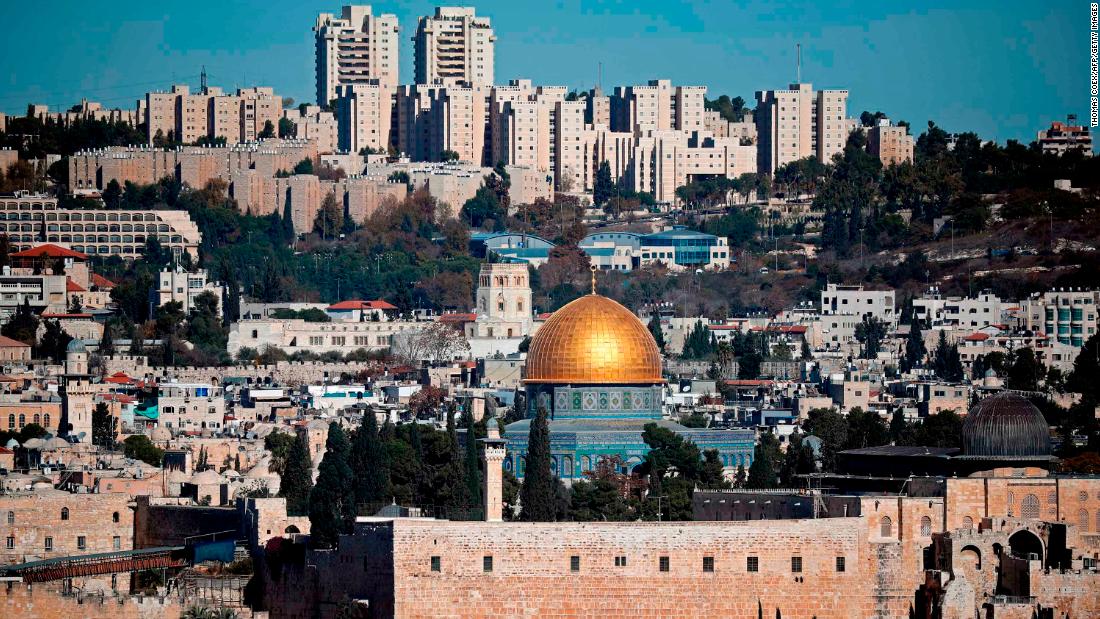

A late-afternoon view of Jerusalem – with the Dome of the Rock, in gold, in the foreground…

* * * *

And speaking of pilgrimages: This May I’ll be making such a two-week journey to Jerusalem. (As part of a local church group.) On that note, Kenneth Clark – the noted British “art historian, museum director, and broadcaster” – discussed the origin of such spiritual journeys in his 1969 TV series, Civilisation. (The following quotes are from the book version, at pages 40-42.)

And speaking of pilgrimages: This May I’ll be making such a two-week journey to Jerusalem. (As part of a local church group.) On that note, Kenneth Clark – the noted British “art historian, museum director, and broadcaster” – discussed the origin of such spiritual journeys in his 1969 TV series, Civilisation. (The following quotes are from the book version, at pages 40-42.)

In Chapter 2 – “The Great Thaw” – Clark noted the “sudden reawakening of European civilization in the 12th century.” (That is, the years from 1101 to 1199 or so.) He said that “great thaw” – the sudden spurt of growth in human development – did not come about from mere idle contemplation. Instead it came as the result of action: “a vigorous, violent sense of movement, both physical and intellectual.”

The physical – action – part took the form of pilgrimages; most often to Jerusalem. That led in turn to the Crusades. (“Traditionally, they [the Crusades] took place between 1095 and 1291;” and of course “the most important place of pilgrimage was Jerusalem.”) But these early pilgrimages were not at all like our “cruises or holidays abroad” today. For one thing they took a long time; often two or three years. “For another, they involved real hardship and danger.”

That is, despite efforts to organize (“pilgrims used to go in parties of 7000 at a time”), “elderly abbots and middle-aged widows often died on the way to Jerusalem.” (Note that our church group requires a doctor’s note from those over 70, saying they “must be able to walk three miles at once at a normal pace” – at least 2-and-a-half miles an hour – “without assistance from others.”)

Another difference: Today such a pilgrimage is typically “a journey to a shrine or other location of importance to a person’s beliefs and faith, although sometimes it can be a metaphorical journey into someone’s own beliefs.” But in those early days, the “point of a pilgrimage was to look at relics.” (On that note, see 2015’s On Peter, Paul – and other “relics.”)

The belief in the “magic” of relics – Clark said – was a product of the Medieval Mind. “The medieval pilgrim really believed that by contemplating a reliquary containing the head or even the fingers of a saint he would persuade that particular saint to intercede on his behalf with God.” (Clark cited an example, Saint Foy, a “little girl of who in late Roman times” was put to death for refusing to worship idols, and then was “turned into one herself.” That is, an idol.*)

In other words, the man with a Medieval Mind believed that by going on a pilgrimage – and in the process venerating relics – he could “get good stuff from God.” Which is of course the same incentive for many practicing Christians today. (If not for those of any religion.) Or as Napoleon put it, “Men are moved by only two things: fear and self-interest.”

In other words, the man with a Medieval Mind believed that by going on a pilgrimage – and in the process venerating relics – he could “get good stuff from God.” Which is of course the same incentive for many practicing Christians today. (If not for those of any religion.) Or as Napoleon put it, “Men are moved by only two things: fear and self-interest.”

But we digress… As seen in the links at the right of this page, I’ve devoted a whole category to Pilgrimages. (Including – the summer of 2018 – I’m back from my Rideau pilgrimage, and – October 2017 – “Hola! Buen Camino!”)

On the topic being discussed, the most relevant blog-post is probably On St. James, Steinbeck, and sluts, from September 2016. That post pointed out that St. James the Greater is the Patron Saint of Pilgrims. And it indicated that on a true pilgrimage – usually by and through “the raw experience of hunger, cold, lack of sleep” – we can “quite often find a sense of our fragility as mere human beings.” And it noted that a true pilgrimage can be “one of the most chastening, but also one of the most liberating” of personal experiences.

In Back from Rideau, the chief ordeal was hour after hour of butt-numbing, back-aching canoe-paddling. In Buen Camino the chief ordeal was hour after hour of hiking, much of it across the dry and dusty Meseta of northern Spain. Which meant sore achy feet and blister upon blister. (At least for the first 250 miles. From León, we mountain-biked the remaining 200 miles. Which just meant different parts of the body got sore, achy and/or blistered.)

So the question for the upcoming trip to Jerusalem: “What part of the trip will help me ‘find a sense of my fragility as a mere human being?'” And “What part of the trip will be ‘most chastening, and also most liberating?’” Or maybe I’ll find somewhere a relic to venerate, and so in turn get some “good stuff from God.” (Aside from being chastened and liberated…)

On that note: Stay tuned! There may well be “further bulletins as events warrant!”

* * * *

On another note, last Monday – March 25 – was the Feast of the Annunciation. See The Annunciation “gets the ball rolling,” from March 2015. The full title is the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the post showed how in this case the early Church “figured it backwards.” That is, they started with the birth of Jesus on December 25, then figured backwards nine months. Since they said Jesus was born on December 25, He had to have been “conceived” on the previous March 25. That’s where the Annunciation comes in.

It celebrates “the announcement by the angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive and become the mother of Jesus, the Son of God, marking his Incarnation.” There’s more on the Incarnation in the post, along with how and why the Conception and Annunciation both got to happen on the same day. Now, about that “getting the ball rolling.”

Technically the liturgical year – the church’s calendar year, illustrated at left – begins with Advent (December 1 or so), and goes through next November. (When it starts all over again.) But it could be argued that the liturgical year properly starts with the Annunciation; that is, the first moment when it became obvious that God would intervene on our behalf, by and through the birth, life and death of Jesus.

Technically the liturgical year – the church’s calendar year, illustrated at left – begins with Advent (December 1 or so), and goes through next November. (When it starts all over again.) But it could be argued that the liturgical year properly starts with the Annunciation; that is, the first moment when it became obvious that God would intervene on our behalf, by and through the birth, life and death of Jesus.

More to the point, the church year “sets out to attune the life of the Christian to the life of Jesus.” (It’s not an “arbitrary arrangement of ancient holy days”):

It is an excursion into life from the Christian perspective [and] proposes to help us to year after year immerse ourselves into the sense and substance of the Christian life… It is an adventure in human growth; it is an exercise in spiritual ripening.

As noted in the “ball rolling” post, I couldn’t have put it better myself. Thus in one sense the Church Year does begin with Advent. On the other hand, you could say that while “technically the liturgical year begins” with Advent, it’s the Annunciation that gets the ball rolling…

And speaking of “getting the ball rolling.” Who knows: My upcoming adventure in Jerusalem will result in some personal “human growth.” At the very least it should be:

“An exercise in spiritual ripening…“

* * * *

‘St. James the Greater, dressed and accoutred as the quintessential Pilgrim…’

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of Jerusalem – Image Results. See also Jerusalem – Wikipedia. Note that the post-title – “On to Jerusalem!” – is an allusion to the Civil War’s famous (or infamous) battle cry, “On to Richmond!” See the National Park Service’s The Focal Point of the Civil War, and Richmond in the American Civil War – Wikipedia.

I cited Clark’s book in On Moses and Paul “dumbing it down:”

Which is another way of saying that all the people who wrote the Bible had to keep in mind the human limitations of their audience. They were trying to put incomprehensible things into plain and simple language that even the most obtuse dolt could understand. Or to paraphrase Sir Kenneth Clark, the people who wrote the Bible had to have the intellectual power to make God comprehensible.

The Kenneth Clark paraphrase is from the hardcover book version of Clark’s Civilisation (TV series). On pages 84-85 of the book, Clark compared the poet Dante with the painter Giotto. Then on page 85, Clark noted the differences between the two men, beginning with the fact that “their imaginations moved on very different planes.” But in the film version – and only in the film or TV version – Clark said Dante had “that heroic contempt for baseness that was to come again in Michelangelo. Above all, that vision of a heavenly order and the intellectual power to make it comprehensible.” Which is the phrase that drew my attention… See also Wikipedia, for more on the TV series.

Clark’s writing about early pilgrimages – especially to Jerusalem – are at pages 40-42 of the book.

Re: The medieval mind. The link is to The Medieval Mind: A Meditation:

The latter [people in the Middle Ages] were drenched in mysticism, whereas the contemporary world has been shaped by rationalism so that mystical concepts and experiences have been stripped away except among a small number of people steeped in the religious thought of our Western ancestors… [Also:] It can be argued that the decline of pilgrimages is a loss to Christian spiritual life in an age of unbelief and immorality when people have a profound need for spiritual examples.

Re: Saint Foy, put to death for refusing to worship idols, then “turned into one herself.” (The “idol” is shown at left.) Clark wrote that she was “obstinate in the face of reasonable persuasion – a Christian Antigone” – and so was martyred. But then her relics began to work miracles,” including the restoration of sight to a man who eyes had been gouged out “by a jealous priest.” As to the little girl whose “relics” were turned into an idol – even though she’d been put to death for refusing to worship idols – “that’s the medieval mind. They care passionately about the truth, but their sense of evidence was different than ours.”

Re: Saint Foy, put to death for refusing to worship idols, then “turned into one herself.” (The “idol” is shown at left.) Clark wrote that she was “obstinate in the face of reasonable persuasion – a Christian Antigone” – and so was martyred. But then her relics began to work miracles,” including the restoration of sight to a man who eyes had been gouged out “by a jealous priest.” As to the little girl whose “relics” were turned into an idol – even though she’d been put to death for refusing to worship idols – “that’s the medieval mind. They care passionately about the truth, but their sense of evidence was different than ours.”

Also, the link in the text is to St. Foy’s Golden Reliquary – Conques, France – Atlas Obscura, about the “huge golden reliquary of a testicle smashing saint.” The article added that “Pilgrims pray to saints for holy intercession in all kinds of problems, but they should be very careful what they ask for when approaching St. Foy, who seems to have a wicked sense of humor.” That is, “St. Foy developed her reputation for… unusual cures. [Ellipses in the original.] Notably, when a knight came to her seeking a cure for a herniated scrotum, she, via vision, helpfully suggested that he find a blacksmith willing to smash it with a white-hot hammer.” See the article for the “rest of the story…”

Also, re “idol.” See Idolatry – Wikipedia: “ldolatry literally means the worship of an ‘idol,’ also known as a worship cult image, in the form of a physical image, such as a statue. In Abrahamic religions, namely Christianity, Islam and Judaism, idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than God as if it were God.” Note the subtle difference to the medieval mind, asking the “saint” in question to intercede with God…

Re: Hiking the Meseta part of the Camino de Santiago: “Many people avoid the Meseta, catching the bus from Burgos to Leon,” while others – who aren’t so wussified – think that misses the whole point of hiking the Camino.

I borrowed the “further bulletins” cartoon from The Transfiguration of Jesus – 2016.

I borrowed the lower image from St. James, Steinbeck, and sluts, from 2016. See also Wikipedia, with full caption, “Saint James the Elder by Rembrandt[.] He is depicted clothed as a pilgrim; note the scallop shell on his shoulder and his staff and pilgrim’s hat beside him.” Also, the “sluts” post noted in part: “Of course the two [pilgrimages] I went on this summer weren’t close to being like going to Jerusalem. (See Back in the saddle again, again.) But for next summer – more precisely, September 2017 – my brother and I plan to hike the Camino de Santiago…” (Can you say foreshadowing?)