Ralph Waldo Emerson, who first said – in essence – “I pity the fool!“

* * * *

March 10, 2015 – That full quote would be (from Emerson), “I pity the fool who doesn’t do pilgrimages and otherwise push the envelope, even at the advance stage of his life.” (Or “words to that effect.”)

Which is another way of saying that this follows up my review of Robert Louis Stevenson’s book Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes. And that’s another way of saying that my brother reviewed the last post that I did on our eight-day canoe trip back in November. (See it at Part II of the post On achieving closure.)

One conclusion was that I’d given undue credence to “the ‘pat-pat’ people of the world.” Which was another version of a quote that actually did come from Emerson, “Whoso would be a man, must be a nonconformist…”

Up to speed: My brother and I did an 8-day canoe trip, starting west of the Rigolets between Lake Ponchartrain and the Gulf of Mexico. We paddled 12 miles out into the Gulf and camped on places like Half-moon Island and Ship Island. (And an occasional salt marsh.)

We ended up in Biloxi under less-than-happy circumstances. (Picked up by a Biloxi Marine Patrol boat due to “inclement weather.”) So, my Part II review was on me trying to “achieve closure” back in February. (I wanted to bring the trip to a de jure happy ending, if not a de facto happy ending.) Back to my brother’s analysis:

Read your blog on the trip and I think there is one point where you give [undue] credence to the view of the “pat-pat” people of the world. The issue is the idea that only people, “not in their right minds,” would go to places (or do things) that are unique experiences – ones that most others never have. In my mind, this is exactly what people in their right mind should be doing. I pity those who don’t.

I agreed with him about the “pat-pat” people, bu the exchange reminded me of Mr. T and his famous phrase. (Here, an imagined quote from Emerson, and below in the more familiar form.) To me the phrase “pity the fool” reflected my true feelings about stay-at-home milquetoasts who would ask, “Why would anyone want to do that?” (As in, “Why would anyone want to take an eight-day primitive-camping canoe trip 12 miles out into the Gulf of Mexico?“) For that matter, why would anyone kayak an hour out into the Gulf of Mexico, just to achieve closure?

I talked about that in Part II. “Last February 8, I drove down to Biloxi, where our eight-day canoe trip ended some three months before. I’d packed my 8-foot kayak in back of my Ford Escape. I got a motel on the beach, and next morning set off in the pre-dawn darkness. (I wanted to close the gap between how we wanted the canoe-trip to end, and how it actually ended.)”

I described that dark morning of February 9, with my “nagging feeling, setting out in the complete darkness, of either going off the edge of the world or being eaten by sharks.” Then came this:

Every once in a while I’d pause, turn off my stop-watch and just enjoy the feeling “of being somewhere, someplace that no one else in his right mind would ever be.” I imagine the explorers back in the olden days had something of the same feeling.

The truth is that I was very happy on that February 9 morning, paddling out from Biloxi Beach, even in the complete darkness. It was peaceful and the sunrise later on was “to die for.” And – every once in a while, especially when I reached the turn-back point – I’d stop paddling, enjoy the ambience and say to myself, “This is what it’s all about.”

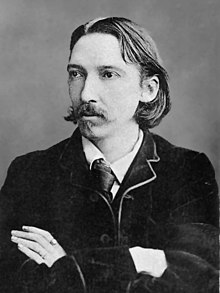

Which brings up some things Robert Louis Stevenson – shown at right – said in his Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes. (See also On donkey travel – and sluts.) My true feelings about such a strenuous pilgrimage – even at the advanced age of 63 – reflected pretty much was Stevenson said in Travels with a Donkey, and what John Steinbeck said in Travels with Charley.

Which brings up some things Robert Louis Stevenson – shown at right – said in his Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes. (See also On donkey travel – and sluts.) My true feelings about such a strenuous pilgrimage – even at the advanced age of 63 – reflected pretty much was Stevenson said in Travels with a Donkey, and what John Steinbeck said in Travels with Charley.

Stevenson’s book recounted a “12-day, 120-mile solo hiking journey through the sparsely populated and impoverished areas of the Cévennes mountains in south-central France in 1878.” The book – “a pioneering classic of outdoor literature” – is said to be the basis for Travels with Charley.

So, at the end of my first review we left Stevenson at page 50 of the 197 pages of his Travels. He’d just run across a “pair of impudent sly sluts, with not a thought but mischief.” (Young girls about 12 from a village of people “but little disposed to counsel a wayfarer.”) Stevenson had to grope in the dark for a campsite; “the scene of my encampment was not only black as a pit, but admirably sheltered.” He ate a crude dinner – a “tin of bologna” and some cake, washed down by brandy – then settled in for the night. “The wind among the trees was my lullaby.”

But he woke in the morning “surprised to find how easy and pleasant it had been,” sleeping in the open, “even in this tempestuous weather.” He then waxed poetic:

I had been after an adventure all my life, a pure dispassionate adventure, such as befell early and heroic voyagers; and thus to be found by morning in a random nook in Gevaudan – not knowing north from south, as strange to my surroundings as the first man upon the earth, an inland castaway – was to find a fraction of my day-dreams realized.

(Pages 50-56, “Upper Gevaudan.”) Stevenson said pretty much the same thing I said in Part II: The dawn and sunrise was “to die for,” and that he too enjoyed the “ambience.” He experienced something that the less-adventurous – then and now – don’t know they’re missing. Something of the feelings explorers back in the olden days had. (Those “early and heroic voyagers…”) On page 64 Stevenson expanded on that thought:

Alas, as we get up in life, and are more preoccupied with our affairs, even a holiday is a thing that must be worked for. To hold a pack upon a pack-saddle against a gale out of the freezing north is no high industry, but it is one that serves to occupy and compose the mind. And when the present is so exacting, who can annoy himself about the future?

Indeed, “who can annoy himself about the future” when immersed in the exacting task of holding a pack atop a stubborn mule and facing a “gale out of the freezing north?” (Or for that matter, “immersed” in paddling for hours on end, 12 miles offshore, at the mercy of the elements, with the day’s end promising nothing but a warm meal on a soggy beach, or salt marsh. Which actually turned out to be quite rewarding…)

That’s the nature of pilgrimages. They give us a break from Real Life, from the rat race of so many today. Which I noted in St. James the Greater. That post quoted a pilgrimage as “ritual on the move.” That through the raw experience of hunger, cold and lack of sleep, “we can quite often find a sense of our fragility as mere human beings, especially when compared with ‘the majesty and permanence of God.'” In short, a pilgrimage can be “‘one of the most chastening, but also one of the most liberating’ of personal experiences.”

It’s hard to get that across to those who would ask, “Why would anyone want to do that?” That’s where the “pity the fool” part comes in. And that reminded of what Ralph Waldo Emerson said: “Whoso would be a man, must be a nonconformist…” See Quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson, and/or Ralph Waldo Emerson – Wikipedia. Also Paragraphs 1-17 – CliffsNotes, a review of Emerson’s Self-Reliance:

Emerson begins his major work on individualism by asserting the importance of thinking for oneself rather than meekly accepting other people’s ideas… The person who scorns personal intuition and, instead, chooses to rely on others’ opinions lacks the creative power necessary for robust, bold individualism.

John Steinbeck said it more diplomatically. He began Part Two of Travels by noting many men his age – told to slow down – who “pack their lives in cotton wool, smother their impulses, hood their passions, and gradually retire from their manhood.” (They “trade their violence for a small increase in life span.”) That wasn’t his way:

I did not want to surrender fierceness for a small gain in yardage… If this projected journey should prove too much then it was time to go anyway. I see too many men delay their exits with a sickly, slow reluctance to leave the stage. It’s bad theater as well as bad living.

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of Ralph Waldo Emerson – Wikipedia.

The original post had a lower image is courtesy of www.jacobswell … pity-the-fool/: the “Jacob’s Well” blog, based in Memphis, Tennessee. Jacob’s Well is “a place where people come together from different racial, economic, and cultural backgrounds to grow in the gospel and work together to overcome racism, addiction, and poverty.” Further:

People who are hurting throughout our city have been turned off by religion and religious people. Jacob’s Well is opening up the doors of a church, but offering a different experience. Those living in poverty have received handouts for years, yet the conditions in our city have only grown worse. At the same time, many enfranchised families desire to alleviate poverty in Memphis yet don’t know anyone personally who is poor. Memphis is thirsty; the living water of Jacob’s Well is plentiful. What better place than here? What better time than now?

Emphasis added. The upshot is that the blogger in Memphis seems to be a “kindred spirit.” He’s trying to undo some of the same damage I am, by reaching out to those “turned off by religion and religious people.” (Though I would add, “so-called religious people.”) For further reading you can Google “faith in action,” with or without “definition” added. See also James 2:14. From there click on the blue “forward” icon to James 2:17. (You just need to take care to avoid the temptation to think that you can “buy your way into heaven” or otherwise “grease the skids.”)

* * * *