“One morning [at] the Louvre,” with Catherine de’ Medici – in black – who authored the massacre…

* * * *

August 24 was the Feast day for St. Bartholomew, also known as Bartholomew the Apostle. Unfortunately, he is perhaps best known for the massacre on his feast day in 1572:

The St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre … in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence, directed against the Huguenots… Though by no means unique, it “was the worst of the century’s religious massacres.” Throughout Europe, it “printed on Protestant minds the indelible conviction that Catholicism was a bloody and treacherous religion.”

This particular massacre occurred during “the French Wars of Religion.” (Those wars lasted some 40 years – beginning in 1562 – and resulted in the deaths of some 3,000,000 people.) A more modern illustration of such “mob violence” is shown above left.

And on a personal note: My French ancestors – who came to America to get the hell away from such religious “conservatives” – were Huguenots. (“French Calvinist Protestants.”)

But before talking more about this one massacre, here’s some information on the saint.

See for example CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Bartholomew. It said “Bartholomaios” means “son of Talmai” (or Tholmai), but that little else is known about him. “Many scholars, however, identify him with Nathaniel.” See for example, John 1:45-51: “Philip found Nathanael and told him, ‘We have found the one Moses wrote about… Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph.'”And so our August 24 “St. Bart” is generally identified as the famous Nathanael who Jesus saw – in the first chapter of the John’s Gospel – sitting under the fig tree.

For more see Bartholomew the Apostle – Wikipedia. It noted a number of traditions about this saint, including that he went on missionary journeys to India, or in the alternative to “Ethiopia, Mesopotamia, Parthia, and and Lycaonia.” But the best known tradition is this:

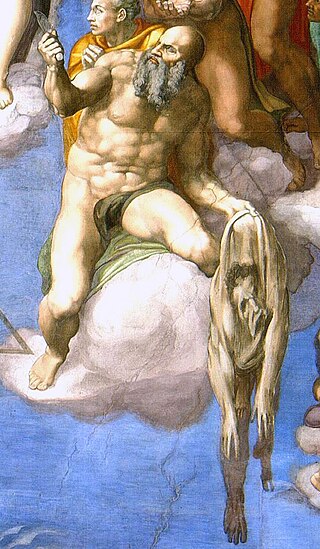

He is said to have been martyred in Albanopolis in Armenia. According to one account, he was beheaded, but a more popular tradition holds that he was flayed alive and crucified, head downward. He is said to have converted Polymius, the king of Armenia, to Christianity. Astyages, Polymius’ brother, consequently ordered Bartholomew’s execution.

Which may mean that if you want to convert one king to Christianity – or some other powerful leader of a country – you probably want to convert all his brothers as well.

For the Bible readings for the day, see St. Bartholomew, Apostle. And there’s a painting at the bottom of the main text – by Michelangelo of “Saint Bartholomew displaying his flayed skin.”

Which brings us back to the St. Bartholomew’s massacre. As Wikipedia noted, in the years since 1572 the massacre “has inevitably aroused a great deal of controversy.” (Adding that “Modern historians are still divided over the responsibility of the royal family,” including Catherine de’ Medici, seen in black in the painting at the top of the page.)

But perhaps the best answer came from Pope John Paul II. In August of 1997, and while in Paris,* he issued a statement on the Massacre:

But perhaps the best answer came from Pope John Paul II. In August of 1997, and while in Paris,* he issued a statement on the Massacre:

On the eve of Aug. 24, we cannot forget the sad massacre of St. Bartholomew’s Day… Christians did things which the Gospel condemns. I am convinced that only forgiveness, offered and received, leads little by little to a fruitful dialogue… Belonging to different religious traditions must not constitute today a source of opposition and tension. On the contrary, our common love for Christ impels us to seek tirelessly the path of full unity.

And speaking of “fruitful dialogue,” the Pope’s comments in 1997 pretty much mirror what the Apostle Paul said in Romans 12:1-8 – the New Testament reading for Sunday, August 27:

For as in one body we have many members, and not all the members have the same function, so we, who are many, are one body in Christ, and individually we are members one of another. We have gifts that differ according to the grace given to us…

In other words, maybe it’s about damn time that we started celebrating our differences. As opposed to flaying each other alive. (Metaphorically or otherwise…)

* * * *

“Saint Bartholomew displaying his flayed skin…”

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre – Wikipedia. The full caption: “‘One morning at the gates of the Louvre,’ 19th-century painting by Édouard Debat-Ponsan. Catherine de’ Medici is in black. The scene from Dubois (above) re-imagined.”

“Note” also that an asterisk in the main text indicates a statement supported by reference detailed in this “notes” section. Thus as to the “modern illustration of mob violence,” the image is courtesy of the mob violence or “riot” link in the first indented paragraph. The caption: “Law enforcement teams deployed to control riots often wear body armor and shields, and may use tear gas.”

The Jesus-and-fig-tree image is courtesy of Jesus, Philip, Nathanael and the Fig Treesacredstory.org.

Re: Pope John Paul II’s 1997 statement. He issued it on August 23, the eve of St. Bartholomew’s Day, in the city where the massacre took place. Note also the poignant painting by “Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais,” who…

…managed to create a sentimental moment in the massacre in his painting A Huguenot on St. Bartholomew’s Day (1852), which depicts a Catholic woman attempting to convince her Huguenot lover to wear the white scarf badge of the Catholics and protect himself. The man, true to his beliefs, gently refuses her.

Googling the phrase “celebrate our differences” got me some 115,000,000 results.

Re: Being “flayed alive.” Wikipedia noted that the practice, “known colloquially as skinning, was a method of slow and painful execution in which skin is removed from the body. Generally, an attempt is made to keep the removed portion of skin intact.” The article added this:

Dermatologist Ernst G. Jung notes that the typical causes of death due to flaying are shock, critical loss of blood or other body fluids, hypothermia, or infections, and that the actual death is estimated to occur from a few hours up to a few days after the flaying. Hypothermia is possible, as skin is essential for maintaining a person’s body temperature, as it provides a person’s natural insulation.

The lower image is courtesy of Wikipedia. The full caption: “Saint Bartholomew displaying his flayed skin in Michelangelo‘s ‘The Last Judgment.'”