* * * *

The next upcoming Feast Day is April 25, the Feast Day for Saint Mark. He actually wrote the first Gospel – chronologically speaking – and also the shortest of the Four Gospels.

On the other hand, for the longest time this short-version was the most “dissed” of the Four Gospels. But then the Gospel of Mark went on to become a kind of Cinderella story.

Garry Wills wrote What the Gospels Meant. It said that for many years the Early Church Fathers pretty much neglected Mark’s Gospel. I.e., Mark was the “least cited Gospel in the early Christian period.” But this Cinderella “got her glass slipper,” beginning in the 19th century.

That’s when Bible scholars finally noticed the other three Gospels all cited material from Mark, but “he does not do the same for them.” The conclusion? Mark started the process and set the pattern of and for the other three Gospels. And as a result of that, since the 19th century Marks’ “has become the most studied and influential Gospel.”

See 2015’s On St. Mark’s “Cinderella story.” (Which added that among other problems, Mark’s written Greek was clumsier and more awkward than the more-polished Greek of Matthew, Luke and John.) But while Mark has long been viewed as the “author of the second gospel,” that doesn’t mean Matthew was written first. As Isaac Asimov noted:

Matthew is [listed] first of the gospels in the New Testament because, according to early tradition, it was the first to be written. This, however, is now doubted by nearly everyone. The honor of primacy is generally granted to Mark … the second gospel in the Bible as it stands.

(Asimov, 770) Then there’s the matter of the symbolism of the Four Evangelists. (“Traditionally, the four Gospel writers have been represented by the following symbols.”) Matthew, author of the ostensible first gospel, is symbolized by a “winged man, or angel.” Luke, who wrote the third gospel, and the Acts of the Apostles, is symbolized by a winged ox or bull: “a figure of sacrifice, service and strength.” John, author of the fourth gospel, is symbolized by an eagle.

Then there’s Mark. “In Christian tradition, Mark the Evangelist, the author of the second gospel is symbolized by a lion – a figure of courage and monarchy.” (See Wikipedia, which added that the “lion also represents Jesus’ resurrection.” That’s because “lions were believed to sleep with open eyes, a comparison with Christ in the tomb.)

There’s also the matter whether Mark’s Gospel – as we know it – really contained the ending as it now reads in most Bibles.. That is, the Great Commission, found in found in Mark 16:14–18. Thus the question: Did Mark really write that ending?

According to some critics … Jesus never speaks with his disciples after his resurrection. They argue that the original Gospel of Mark ends at [Mark 16:8] with the women leaving the tomb (see Mark 16).

Note that Mark 16:8 says, “they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.” Which would of course be a bad place to end a Gospel of hope.*

Or see Mark 16 – Wikipedia, “Modern versions … generally include the Longer Ending, but place it in brackets or otherwise format it to show that it is not considered part of the original text.”

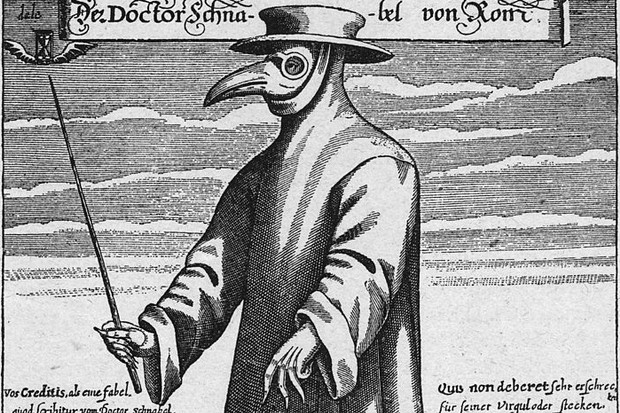

In plain words, it seems that Mark originally wrote his Gospel at a time of great suffering in the early church. And that later redacters felt that original was too bleak; it didn’t offer enough hope. Be that as it may – and as Asimov noted (902) – Mark’s Gospel was designed “to circulate among Christians the story of the sufferings of Jesus and his steadfastness under affliction. Perhaps this was in order to encourage Christians at a time when they, generally, were undergoing persecution.”

And that earthly suffering – that “persecution” – may well be mirrored in the unforeseen and largely inexplicable “end times” that we seem to be suffering through today. (“Who could foresee the coming of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic?”) So what could be the point of that shorter ending? One thing the Mark 16 – Wikipedia article noted:

Mark’s narrative as we have it now [ending at Mark 16:8] ends as abruptly as it began. There was no introduction or background to Jesus’ arrival, and none for his departure. No one knew where he came from; no one knows where he has gone; and not many understood him when he was here.

It went on to say that Mark’s Gospel “becomes the story of his followers, and their story becomes the story of the readers. Whether they will follow or desert, believe or misunderstand, see him in Galilee or remain staring blindly into an empty tomb, depends on us.”

And so it might be today. Maybe the point is that both today’s Covid-19 “persecution” and Jesus’ seemingly unexplained death – with “Mark” ending at Mark 16:8 – have the capacity to be mysteries. “Mysteries” that are a part of life, or the challenges by which we can learn, develop and grow stronger, spiritually and otherwise.

And so both the solution to Mark’s mysterious “shorter ending” and the outcome of today’s Covid-19 affliction may largely “depend on us.” What will we do with this unexpected calamity? Will we go forward and grow stronger, or turn back the clock and start turning on each other?

As variously defined, a mystery can be “something secret or unexplainable;” or something of a puzzling nature; or a secret or mystical meaning; or finally, a “religious truth not understandable by the application of human reason alone (without divine aid).”

In other words, the terribly anguished – and arguably original – ending of Mark‘s Gospel at 16:8 is (according to Pagels), “nevertheless not the ending… [T]here’s a mystery in it, a divine mystery of God’s revelation that will happen yet. And I think it’s that sense of hope that is deeply appealing.” Which sounds a bit convoluted and not very helpful.

But one answer may come in 2016’s On St. James, Steinbeck, and sluts. That post talked about pilgrimages in general – and society’s rituals – and what we can learn from them. For one thing, it noted the book Passages of the Soul: Ritual Today, by James Roose-Evans.

That book said that a healthy sense of ritual “should pervade a healthy society,” and that a big problem now is that “we’ve abandoned many rituals that used to help us deal with big change and major trauma.” And you could easily call our present Covid-19 pandemic both a “big change and [a] major trauma.” The book added that all true ritual “calls for discipline, patience, perseverance, leading to the discovery of the self within.”

In other words, through discipline, patience and perseverance we can discover things within ourselves – from this latest pandemic – that we would never have known otherwise. As for a “pilgrimage,” it can may be described “as a ritual on the move.”

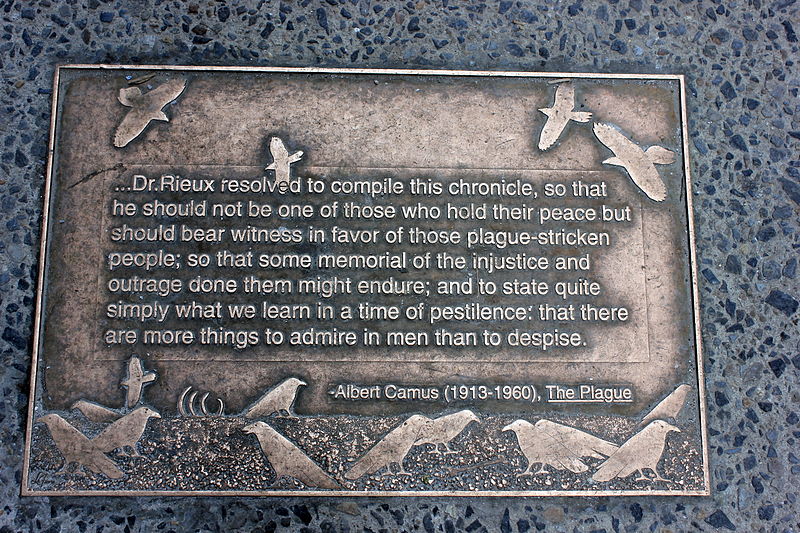

The key point there is that – in any pilgrimage, like the one we’re going through with today’s “plague” – we can “quite often find a sense of our fragility as mere human beings.” And if nothing else, Covid-19 reminds us of our “fragility as human beings.” Which brings us to The Plague by Camus, and a quote from Part 1, early in the book:

Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.

Which certainly seems true of this latest pestilence. It certainly came as a surprise. Then too there’s this recent Salt Lake Tribune review of “The Plague,” with this relevant point:

Being alive always was and will always remain an emergency; it is truly an inescapable “underlying condition…” This is what Camus meant when he talked about the “absurdity” of life. Recognizing this absurdity should lead us not to despair but to a tragicomic redemption, a softening of the heart, a turning away from judgment and moralizing to joy and gratitude.

One possible lesson? The current pestilence might lead to a massive change in our present national life, and especially our national political life. The present Coronavirus might lead to a general and sweeping American “softening of the heart.”

Along with “a turning away from judgment and moralizing to joy and gratitude.” Or even a realization that there “are more things to admire in [all] people than to despise…”

* * * *

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of Peter Paul Rubens: The Four Evangelists, which noted: “Rubens portrayed the four evangelists while working together on their texts. An angel helps them… Each gospel author can be identified by an attribute. The attributes were derived from the opening verses of the gospels. From left to right: Luke (bull), Matthew (man [angel]), Mark (lion), and John (eagle).” See also Four Evangelists – Wikipedia – included as a link in the top image – and/or Harry Truman and the next election.

I borrowed some text and images from 2015’s On St. Mark’s “Cinderella story,” 2016’s More on “arguing with God” – and St. Mark as Cinderella.

The Cinderella image is courtesy of Cinderella – Image Results. Also, for more “theology,” see The Theology of Mark’s Gospel | Preaching Source.

Re: “Asimov, 770,” etc. Referring to Asimov’s “Guide to the Bible: Two Volumes in One.” (Avenel Books, 1981.)

Re: “Bad place to end this Gospel of hope.” For an extended and learned analysis, see Did Mark Write Mark 16:9-20? A Textual Criticism Case Study. Or Google “mark 16:9-20 controversy.”

Re: “Mark 16:8, 4th C.” From Mark 16 – Wikipedia, full caption: “Mark ends at 16:8 in the 4th-century Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209.”

The lower image is courtesy of The Plague – Wikipedia.