The Virgin Mary in prayer – by Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato, “c. 1650.”

* * * *

Today – May 31 – is the feast day dedicated to the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. (As it’s formally known.) See also Visitation (Christianity) – Wikipedia, which noted:

The Visitation is the visit of Mary with Elizabeth as recorded [in] Luke 1:39–56. It is also the name of a Christian feast day[,] celebrated on 31 May… Mary is pregnant with Jesus and Elizabeth is pregnant with John the Baptist. Mary left Nazareth immediately after the Annunciation and went “into the hill country” [of Judah] to attend to her cousin.

Wikipedia added, “In the Gospel of Luke, the author’s accounts of the Annunciation and Visitation are constructed using eight points of literary parallelism to compare Mary to the Ark of the Covenant.” (Which I didn’t know.) And the Blessed Virgin Mary article added that Elizabeth greeted Mary with the words, “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb.” Mary responded with what became known as Magnificat. In turn:

John the Baptist, still unborn, leaped for joy in his mother’s womb. Thus we are shown, side by side, the two women, one seemingly too old to have a child, but destined to bear the last prophet of the Old Covenant … and the other woman, seemingly not ready to have a child, but destined to bear the One Who was Himself the beginning of the New Covenant, the age that would not pass away. (E.A.)

And speaking of Mary, see the post On St. Mary, Mother. Among other things, it noted that “In Renaissance paintings especially, Mary is portrayed wearing blue, a tradition going back to the Byzantine Empire … where blue was ‘the color of an empress.’”

Another explanation comes from “Medieval and Renaissance Europe,” where…

…the blue pigment was derived from the rock lapis lazuli, a stone imported from Afghanistan of greater value than gold. Beyond a painter’s retainer, patrons were expected to purchase any gold or lapis lazuli to be used in the painting. Hence, it was an expression of devotion and glorification to swathe the Virgin in gowns of blue. (E.A.)

Which explains Mary being shown in blue in the painting at the top of the page.

That post also noted that the Magnificat “echoes” several Old Testament passages, including allusions to “the Song of Hannah,” in 1st Samuel 2:1-10. (Not to mention “the Book of Odes, an ancient liturgical collection…”)

That post also noted that the Magnificat “echoes” several Old Testament passages, including allusions to “the Song of Hannah,” in 1st Samuel 2:1-10. (Not to mention “the Book of Odes, an ancient liturgical collection…”)

See also On the psalms up to December 21, which included the image at right. (Of Mary, reciting the Magnificat.)

That post included a note that Mary’s hymn of praise was “distilled from a collection of early Jewish-Christian canticles,” and patterned in turn on the “‘hymns of praise’ in Israel’s Psalter.” In turn, “Mary symbolizes both ancient Israel and the Lucan faith-community.” (That is, the particular “faith community” that Luke addressed in his Gospel.)

And finally, some notes from Isaac Asimov.

Among other things, he noted the apparent ongoing competition between the two men – Jesus and John the Baptist – or at least between or among their followers. (See e.g. John 3:22-36 Competition in Ministry and Were Jesus and John the Baptist Competitors?)

Which may explain why Luke – and he alone, in his Gospel – included the episode of Mary’s “visitation.” His goal may have been to show that – even in the womb – John the Baptist “recognized Jesus’ priority and transcendant importance… This would be a strong point for the followers of Jesus and against the competing followers of John.”

Asimov too noted that Mary’s “hymn of praise” – starting at Luke 1:46 – was very much like that of Hannah, “on the occasion of her giving birth to Samuel, and is widely considered to be inspired by it.” (See 1st Samuel 2, 1-10, which begins, ““My heart rejoices in the Lord; in the Lord my horn is lifted high. My mouth boasts over my enemies, for I delight in your deliverance.”)

Asimov also noted that Elizabeth and Hannah were more alike than Mary. Mary was young and “unmarried,” while both Elizabeth and Hannah were old and had been married many years, “in a society that considered barrenness a punishment for sin.” Thus they were “blessed by a pregnancy, in old age and after many years of marriage,” and thus were vindicated.

But we digress…

(As shown at left, with Jesus as a young boy…)

One big factor seemed to be Matthew’s preaching to pious Jews, who could understand his ongoing citations to the Old Testament in his Gospel. But Luke had another audience in mind:

The Gentiles knew of goddesses, and their pagan religions often had a strong feminine cast. If Luke were a Gentile, he would be drawn to the tales Mary. Matthew, on the other hand, a product of the strongly patriarchal Jewish culture, would automatically deal with Joseph.

Or as Asimov put it, Matthew aimed his Gospel for those “learned in Old Testament lore.” Luke on the other hand wrote his Gospel for Gentiles, translated alternately as “Goy,” non-Jews, or “outsiders.” That is, he wrote for those outsiders who were “considering conversion” – to Christianity – “or perhaps are already converted and wish to know still more concerning the background of their new religion.”

In turn, Jesus Himself is “portrayed as far more sympathetic to Gentiles in Luke than in the other Synoptic Gospels.” (And a good thing too, I might add.)

So today we celebrate this early meeting of Mary and cousin Elizabeth. “Their meeting sets the stage for all that will come later, and it is women who recognize it first.”

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of the Marian perspectives link at Mary, mother of Jesus – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. The caption: “The Virgin in Prayer, by Sassoferrato, c. 1650.” (Or in the alternative: “Jungfrun i bön (1640-1650). National Gallery, London.”)

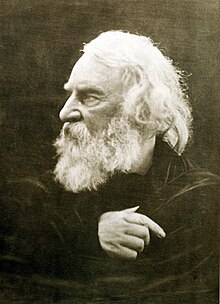

The Isaac Asimov quotes-and-notes are from Asimov’s Guide to the Bible: Two Volumes in One, the Old and New Testaments, Avenel Books (1981), at pages 914 and 920-21, with emphases added.

Asimov (1920-1992) was “an American author and professor of biochemistry at Boston University, best known for his works of science fiction and for his popular science books. Asimov was one of the most prolific writers of all time, having written or edited more than 500 books and an estimated 90,000 letters and postcards.” His list of books included those on “astronomy,mathematics, the Bible, William Shakespeare’s writing, and chemistry.” He was a long-time member of Mensa, “albeit reluctantly; he described some members of that organization as ‘brain-proud and aggressive about their IQs.’” See Wikipedia.

Asimov also noted the “legend” that Luke knew Mary personally, “and learned of the story of Jesus’ birth from her in her old age.” He also noted the tradition – in his view, unsupported – that “Luke was an artist and painted a portrait of Mary that was later found in Jerusalem.”

The Joseph-and-Jesus painting is “St. Joseph the Carpenter, by Georges de La Tour, 1640s.”

Also last year at this time I did

Also last year at this time I did  And finally, note

And finally, note

That reading included

That reading included

(For a more “worldly” view on

(For a more “worldly” view on  But because of all those “mysteries” in the Bible, it takes awhile to understand. (A lifetime “and more,” in fact.) And that’s just another way of saying, sometimes we just

But because of all those “mysteries” in the Bible, it takes awhile to understand. (A lifetime “and more,” in fact.) And that’s just another way of saying, sometimes we just

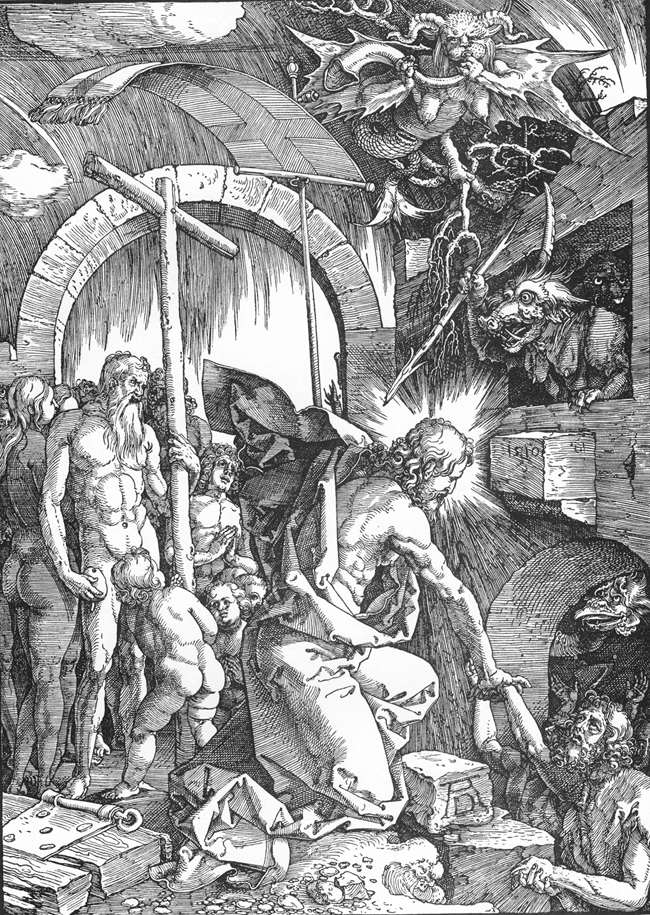

Before Jesus could Ascend into Heaven, He had to Descend into Hell…

Before Jesus could Ascend into Heaven, He had to Descend into Hell… Note that the 40-day calculation is from

Note that the 40-day calculation is from  That was the name of a 1944 song performed by

That was the name of a 1944 song performed by  For a more

For a more

The

The  In turn,

In turn,  There’s a similar gem in the

There’s a similar gem in the  I wrote about these passages in

I wrote about these passages in  (156-57) And incidentally, one of those “attractions of surrounding cultures” was

(156-57) And incidentally, one of those “attractions of surrounding cultures” was  You can see more background on “Azazel” in

You can see more background on “Azazel” in

See also the

See also the