Rabia Basri, female Muslim saint and mystic.

Welcome to the DORscribe website, just chock-full1 of Bible-reading previews, color commentary, and “deep background.”

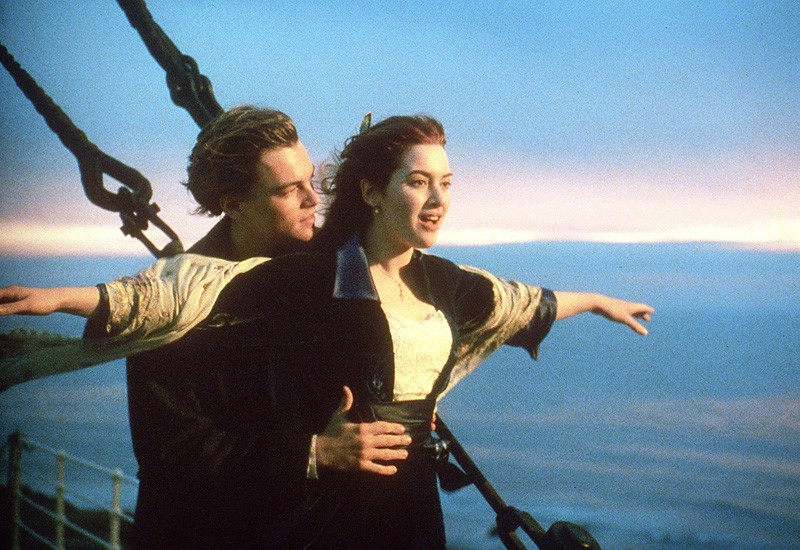

This morning’s post involves a parable, the kind of story that Jesus used to tell.

“Once upon a time,” there was a woman of great wealth and power. She was courted by three different men, and each wanted to marry her.

She spent time with the first man. After much urging that he be “totally honest,” the first man made a candid admission: he was on probation, and had been ordered to find a good woman, get married and settle down. So (the suitor admitted), he wanted to marry the rich woman so he wouldn’t have to go through the hell of prison life.

The woman decided to get to know the second suitor. Again after much urging to be honest, the second man admitted he wanted to marry her so he could be “on easy street.” He was tired of all the garbage of his everyday life. The main thing he looked forward to (once they were married) was taking things easy and not grubbing for a living, as his “previous life.”

Finally, the woman got to know the third man better. When he got totally honest, he said while he might enjoy sharing the woman’s wealth and power, that didn’t really matter to him; she was special and that was that. He couldn’t imagine living his life without her, now that he’d gotten to know her. It wouldn’t matter to him if she didn’t have any money, or didn’t want to share what she did have. He’d still love her and want to be with her, even if it meant living in a hovel. He wanted to be near her and share his life with her.

All of which brings up a prayer said to come from the Koran:

O God, if I worship Thee in fear of hell, burn me in hell; if I worship Thee in hope of Paradise, exclude me from Paradise; but if I worship Thee for Thine own sake, withhold not Thine everlasting beauty.

That prayer might remind us that maybe there’s more to praying than just asking God for a bunch of goodies (or a Mercedes Benz), like a spoiled child. And by the way, that prayer apparently didn’t come from the Koran, but came from “a Muslim woman named Rabia in the 8th century.” One website said the essence of this kind of prayer is “praise rather than petitioning, an attempt to go beyond the requirements of ritual worship by adoring God.”

Which brings us back to the parable of the woman and her three suitors.

First, assume for the sake of the parable that each man told the truth. (Which many women would say is no small assumption). Then the question would be: which man showed the greater true love? And finally, if you were that woman, which man would you choose?

* * * *

Which brings up some problems in interpreting the Bible.

For one thing, there’s the Hebrew style of writing; in Hebrew there are no vowels, and the letters of a sentence are strung together. An example: a sentence in English, “The man called for the waiter.” Written in Hebrew, the sentence would be “THMNCLLDFRTHWTR.” But among other possible translations, the sentence could read, in English, “The man called for the water.”

Another problem with interpreting “the law of the Bible” is that most of Jesus’ teachings came in the form of parables, like the one above.

The book Christian Testament said parables are “very much an oral method of teaching,” and that in such an oral tradition, it was up to the listener to decipher the meaning of the parable, to him. Or as Jesus said on several occasions, “Whoever has ears to hear, let them hear.”

The problem came when these oral-tradition parables were written down, at a minimum some 20 years after the fact, as in Mark’s Gospel. Quite often, in transposing the parable from oral to written form, it needed an interpretation added to it. (In Hebrew the word for such interpretation is nimshal, or the plural, nimshalim.) That in turn could lead to some uncertainty.

But Christian Testament said this “uncertainty” doesn’t necessarily present a problem:

The essence of the parabolic method of teaching is that life and the words that tell of life can mean more than one thing. Each hearer is different and therefore to each hearer a particular secret of the kingdom [of God] can be revealed. We are supposed to create nimshalim for ourselves.

(CT, 321) All of which seems to be one of those ideas that can give a conservative Christian apoplexy; the fact the Bible might mean different things to different people. Put another way, just as it seems unreasonable to say God died for one person (or one set of people), it seems just as unreasonable to say that the Bible must mean the same thing to everyone, all the time.

Which brings up the Christians who insist that the Bible must be interpreted literally, and only literally. More to the point, if and when you read the Bible, which style of interpretation would you prefer? A literal, strict and/or narrow interpretation? Or would you prefer a more open-minded or even – gasp! – liberal interpretation, so as to implement the object and purpose of the document? (That intent can arguably be found in John 10:10, where Jesus said, “My purpose is to give life in all its fullness.”)

That in turn raises a couple more questions, like: How do you “strictly interpret” a parable, or for that matter, how do you strictly interpret “THMNCLLDFRTHWTR?”

“Clarence Darrow (left) and William Jennings Bryan chat in court during the Scopes Trial.” Image and quote courtesy of Wikipedia, which explained this as a famous 1925 American legal case – also known as the “Monkey Trial” – in which a “substitute high school teacher, John Scopes, was accused of violating Tennessee’s Butler Act, which made it unlawful to teach human evolution in any state-funded school” (which sounds an awful lot like “deja vu all over again.”

Bryan was called in as a special prosecutor, in part at the behest of the World Christian Fundamentals Association. Darrow volunteered his services to the defendant Scopes. The trial covered by famous journalists from arund the world, including H. L. Mencken of The Baltimore Sun. “It was also the first United States trial to be broadcast on national radio.”

Other references:

According to one online definiton, the term “chock-full” seems to come from the Middle English chokkefull, probably from choken to choke + full, with the “First Known Use: 15th century.”

The image of Rabia Basris is courtesy of http://sufipoetry.files.wordpress.com/2009/12/rabia.jpg?w=500. See also Rabia Basri – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

As to “a parable [like] Jesus used to tell.” See Matthew 13:34 (ESV): “All these things Jesus said to the crowds in parables; indeed, he said nothing to them without a parable.”

As to “in Hebrew there are no vowels.” See Education for Ministry, Year One (Hebrew scriptures) 4th Edition, Charles Winter and William Griffin (1990).

As to “Christian Testament [saying] parables are “very much an oral method of teaching.” See Education for Ministry Year Two (Hebrew Scriptures, Christian Testament) 2nd Edition by William Griffin, Charles Winters, Christopher Bryan and Ross MacKenzie (1991).

As to the differences between a strict or narrow construction, (as opposed to a more “liberal” construction or interpretation), see: Legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/strict+construction. Another site that might be of interest: A Quaker’s Response to Christian Fundamentalism.

The strange thing about Ira Louvin – at right in the picture at left – is that he “was notorious for his drinking, womanizing, and short temper.” (Or maybe it wasn’t so strange after all.) Ira ended up getting married four times, and his third wife Faye ended up shooting him six times. (Four times in the chest.) That was after one of the times he allegedly beat her up.

The strange thing about Ira Louvin – at right in the picture at left – is that he “was notorious for his drinking, womanizing, and short temper.” (Or maybe it wasn’t so strange after all.) Ira ended up getting married four times, and his third wife Faye ended up shooting him six times. (Four times in the chest.) That was after one of the times he allegedly beat her up. And to many people it offers a better path to the type of abundance Jesus promised in John 10:10. That Bible path is exemplified by

And to many people it offers a better path to the type of abundance Jesus promised in John 10:10. That Bible path is exemplified by

Another question: If Jesus was a

Another question: If Jesus was a  Collins said that at first he thought Jesus was talking about people in Matthew (as “plain meaning” would require). But he changed his mind after considering “

Collins said that at first he thought Jesus was talking about people in Matthew (as “plain meaning” would require). But he changed his mind after considering “

That’s the problem.

That’s the problem.

/Getty_irony-556724397-56a3cb205f9b58b7d0d3cbea.jpg)

So, in pretty much the same way that Abraham heard The Voice that told him to leave his homeland – at 75 years of age or so – Jesus may have first become aware of His being special by also “hearing a voice,” or voices…

So, in pretty much the same way that Abraham heard The Voice that told him to leave his homeland – at 75 years of age or so – Jesus may have first become aware of His being special by also “hearing a voice,” or voices…