“The Calling of St. Matthew,” by Hendrick ter Brugghen, as described in Matthew 9:9-13…

* * * *

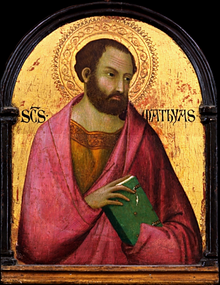

The next major feast day – after September 14’s Holy Cross Day – is September 21, for St. Matthew, Evangelist. I wrote about him and his feast day in On St. Matthew – 2015. (Which included the image at right, of Matthew as an old man.) Back in 2014 I posted On St. Matthew.

The next major feast day – after September 14’s Holy Cross Day – is September 21, for St. Matthew, Evangelist. I wrote about him and his feast day in On St. Matthew – 2015. (Which included the image at right, of Matthew as an old man.) Back in 2014 I posted On St. Matthew.

Both are based in large part on Matthew 9:9-13:

As Jesus went on from there, he saw a man named Matthew sitting at the tax collector’s booth. “Follow me,” he told him, and Matthew got up and followed him. While Jesus was having dinner at Matthew’s house, many tax collectors and sinners came and ate with him and his disciples. When the Pharisees saw this, they asked his disciples, “Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?” On hearing this, Jesus said, “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. But go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ For I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.”

Which turned out to be good news for pretty much all of us. (He said, tongue-in-cheek.)

See also the Satucket article on St. Matthew, which noted that in Jesus’ time tax collectors – like Matthew – were “social outcasts. Devout Jews avoided them because they were usually dishonest (the job carried no salary, and they were expected to make their profits by cheating the people from whom they collected taxes).” Which led to this:

See also the Satucket article on St. Matthew, which noted that in Jesus’ time tax collectors – like Matthew – were “social outcasts. Devout Jews avoided them because they were usually dishonest (the job carried no salary, and they were expected to make their profits by cheating the people from whom they collected taxes).” Which led to this:

Thus, throughout the Gospels, we find tax collectors (publicans) mentioned as a standard type of sinful and despised outcast. Matthew brought many of his former associates to meet Jesus, and social outcasts in general were shown that the love of Jesus extended even to them.

(Emphasis added.) See also Tax collector – Wikipedia, and the Wikipedia article on tax farmers. And as noted in 2014’s On St. Matthew, such a tax collector as Matthew was “sure to be hated above all men as a merciless leech who would take the shirt off a dying child.” Further, in Jesus’ time “the word ‘publican’” – or tax collector – was “used as representing an extreme of wickedness in the Sermon on the Mount.”

(See e.g., Matthew 5:46, in the NIV: “If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Are not even the tax collectors doing that?” In the NLT: “If you love only those who love you, what reward is there for that? Even corrupt tax collectors do that much.”)

As to the “Cinderella” part of the post-title, see St. Mark’s “Cinderella story.” The thing is, Mark wrote the first Gospel, but for years that honor was given to Matthew. (That’s why his Gospel is listed first.)

Matthew is first of the gospels in the New Testament because, according to early tradition, it was the first to be written. This, however, is now doubted by nearly everyone. The honor of primacy is generally granted to Mark, which is the second gospel in the Bible as it stands.

In other words, Mark’s is – or was – the most “dissed” of the Gospels…

That is, for many centuries the Early Church Fathers pretty much neglected Mark’s Gospel. St. Augustine for one called Mark “the drudge and condenser” of Matthew.

For one thing, Mark’s written Greek was “clumsier and more awkward” than the more-polished Matthew, Luke and John. As a result, Mark’s was the “least cited Gospel in the early Christian period.” But “this Cinderella got her glass slipper,” beginning in the 19th century. That’s when Bible scholars finally noticed the other three Gospels all cited material from Mark, but “he does not do the same for them.”

As a result of that conclusion – that Mark wrote the first Gospel – since the 19th century Marks’ “has become the most studied and influential” of the four Gospels.

And so, on September 21 we remember the work of St. Matthew. But we also need to remember the man “on whose shoulders he stood.” (St. Mark, whose work was long disregarded and disrespected. The man who finally – after 1,800 years – got his props.)

There’s an object lesson there, and it probably has to do with the value of teamwork.

As in, “We’re All in This Together!”

* * * *

St. Mark, by Hendrick ter Brugghen…

St. Mark, by Hendrick ter Brugghen…

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of Brugghen, Hendrick ter – The Calling of St. Matthew. See also Matthew the Apostle – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Re: “We’re all in this together!” The link is to the lyrics from a song in the 2006 High School Musical. (See Wikipedia.) But the larger meaning has to do with the current process of electing a new president, for a term to begin in 2017. And that’s not to mention political gridlock in general.

Re: “We’re all in this together!” The link is to the lyrics from a song in the 2006 High School Musical. (See Wikipedia.) But the larger meaning has to do with the current process of electing a new president, for a term to begin in 2017. And that’s not to mention political gridlock in general.

The lower image is courtesy of “Ter Brugghen … Rembrandt’s Room. See also Hendrick ter Brugghen – Wikipedia, on the Dutch painter (1588-1629), a “leading member of the Dutch followers of Caravaggio – the so-called Dutch Caravaggisti.” Also:

His paintings were characteristic for their bold chiaroscuro technique – the contrast produced by clear, bright surfaces alongside sombre, dark sections – but also for the social realism of the subjects, sometimes charming, sometimes shocking or downright vulgar.

For more information on other paintings of “St. Mark,” see FRANS HALS ST MARK – Colnaghi, a PDF file with the full title, “Frans Hals’ St. Mark[:] A Lost Masterpiece Rediscovered.” The article compared paintings done of St. Mark by Ter Brugghen, Hals and others, as well as their common “painterly conventions.” For example, the article said Mark is commonly shown “writing on a scroll” and that Mark and John “tend often to be portrayed as the more mystical figures among the Evangelists.”