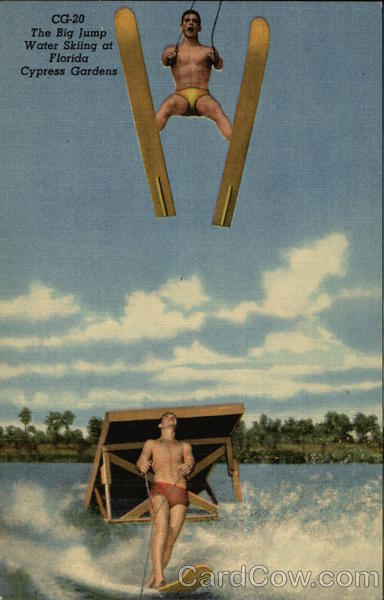

Bathsheba taking a bath – with David watching – “from his balcony (top left)…”

* * * *

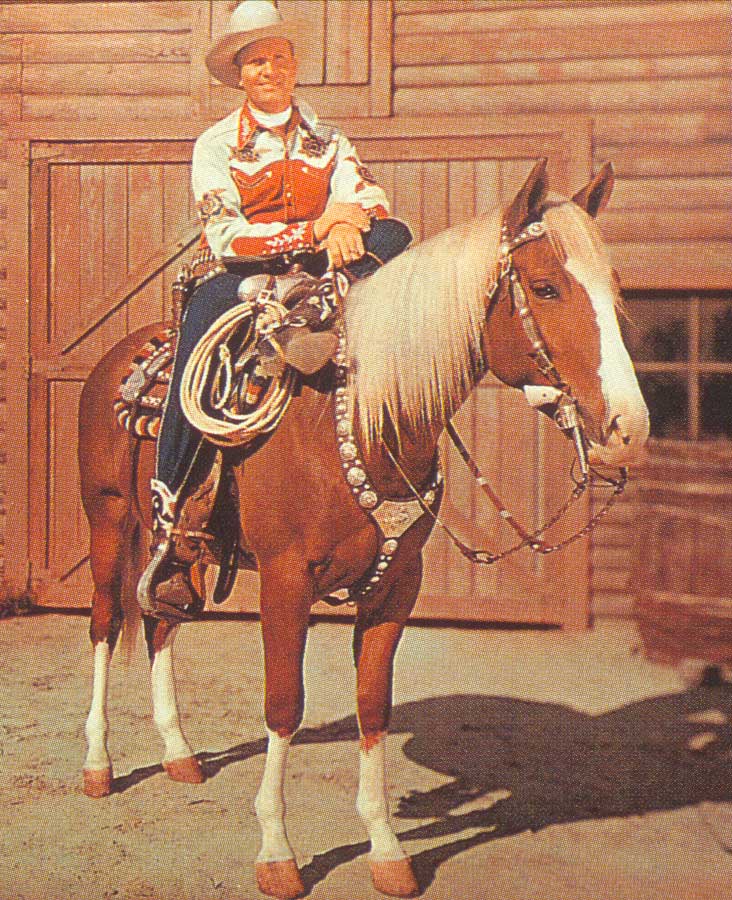

As the last post noted, it’s been a busy several weeks since July 23, when I left God’s Country. (The ATL.) I spent almost six weeks hiking the Chilkoot Trail – “meanest 33 miles in history” – and canoeing 440 miles on the “mighty Yukon River.” I got home on August 29, and since then have written one post, “Back in the saddle again,” again.

As the last post noted, it’s been a busy several weeks since July 23, when I left God’s Country. (The ATL.) I spent almost six weeks hiking the Chilkoot Trail – “meanest 33 miles in history” – and canoeing 440 miles on the “mighty Yukon River.” I got home on August 29, and since then have written one post, “Back in the saddle again,” again.

Now it’s time to start back with a bang, which explains the painting at the top of the page. “Which is being interpreted:”

In case you were wondering, you can find one set of Bible readings for this upcoming Sunday – September 11 – at Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost – Proper 19. Those readings include Psalm 51:1-11, which I wrote about in The readings for July 26. That post included the painting above, of David watching Bathsheba taking a bath. And one result of that encounter was that David wrote Psalm 51. (Because he felt so guilty…)

In writing Psalm 51, “David threw himself on the mercy of God after committing adultery and murder… His two-fold repentance provides a model that we should follow.”

You can see the story behind Psalm 51 at 2d Samuel 11:1-15. It tells how David – after he became King of Israel – came to see Bathsheba taking a bath “in the altogether:”

It also tells what David did to Uriah the Hittite, Bathsheba’s husband. (After he – David – got her pregnant.) When Bathsheba told him about that, David had Uriah brought back from the war and tried to trick him into knowing her in the Biblical sense. (That way, Uriah would think that the kid was his.) When that didn’t work, David basically had Uriah killed. (But he made it look like an accident.) And it was because of all this that David wrote Psalm 51, “by any measure, one of the best-known and most often read penitential texts” in the Bible.

But from there this Sunday’s Bible readings get a lot more cheerful.

For example, the Gospel is Luke 15:1-10. It includes Jesus telling both the Parable of the Lost Coin – shown at right – and the Parable of the Lost Sheep. (And believe me, there were times I felt like a “lost sheep” hiking the “Chilkoot &^%$ Trail.”) But we digress…

For example, the Gospel is Luke 15:1-10. It includes Jesus telling both the Parable of the Lost Coin – shown at right – and the Parable of the Lost Sheep. (And believe me, there were times I felt like a “lost sheep” hiking the “Chilkoot &^%$ Trail.”) But we digress…

As far as feast days go, coming up on September 14 is Holy Cross Day.

As Wikipedia noted, “there are several different Feasts of the Cross, all of which commemorate the cross used in the crucifixion of Jesus.” And within the Church as a whole – Eastern and Western – such Feasts of the Cross are celebrated on various days: like October 12, March 6, May 3, and August 1.

What they have in common is celebrating “the cross itself, as the instrument of salvation.” The Feast Day on September 14 is known by different names, including – in Greek, translated – “Raising Aloft of the Honored and Life-Giving Cross.” However, in the Anglican Communion the feast is called Holy Cross Day, “a name also used by Lutherans.”

For more see Holy Cross Day, on the Satucket or Daily Office Reading* website. It noted that this was a day for recognizing the Cross as a “symbol of triumph, as a sign of Christ’s victory over death, and a reminder of His promise, ‘And when I am lifted up, I will draw all men unto me.’” (John 12:32.) And the article noted that this practice goes back a long time:

Tertullian [seen below left] around AD 211, says that Christians seldom do anything significant without making the sign of the cross… The Cross is the personal mark of Our Lord Jesus Christ, and we mark it on ourselves as a sign that we belong to Him… [Or] as one preacher has said, if you were telling someone how to make a cross, you might say … “Draw an I and then cross it out.”

See the day’s Bible readings – in the “RCL” – at Holy Cross Day: Isaiah 45:21-25, Psalm 98, Philippians 2:5-11, and John 12:31-36a.

See the day’s Bible readings – in the “RCL” – at Holy Cross Day: Isaiah 45:21-25, Psalm 98, Philippians 2:5-11, and John 12:31-36a.

Of particular interest is Psalm 98:1, “Sing to the Lord a new song, for he has done marvelous things.” I noted the implications of Psalm 98:1 in the post, Singing a NEW song to God.

The gist of which is this: “How can we do greater works than Jesus if we interpret the Bible in a cramped, narrow, strict and/or limiting manner? For that matter, why does the Bible so often tell us to ‘sing to the Lord a new song?’” (See also Isaiah 42:10 and Psalms 96:1, 98:1, and 144:9.)

Getting back to the Feast of the Cross, Wikipedia added this note, on how Constantine‘s mother found the “True Cross,” and in passing about the value of pilgrimages in general:

According to legends that spread widely, the True Cross was discovered in 326 by Saint Helena, the mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great,* during a pilgrimage she made to Jerusalem.

And speaking of pilgrimages: Of course the two I went on this summer weren’t close to being like going to Jerusalem. However, for next summer – or more precisely, September 2017 – my brother and I plan to hike the Camino de Santiago, mostly in Spain.

I’ll talk more about that – and pilgrimages in general – in St. James, Steinbeck, and sluts…

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of David and Bathsheba – The Life and Art of Artemisia Gentileschi. The painting was done in 1650. The full caption:

Pretty Bathsheba has finished her bath. She is fixing her hair, using the mirror held by a servant… Perhaps she has already received King David’s message. David has been watching her from his balcony (top left) and asks her to pay him a visit.

Gentileschi (1593-1656) was a woman artist in an “era when women painters were not easily accepted by the artistic community or patrons.” She was the first woman to become a member of the Accademia di Arte del Disegno in Florence, and painted “many pictures of strong and suffering women from myth and the Bible – victims, suicides, warriors.”

Her best-known work is Judith Slaying Holofernes, which is pretty gruesome. It shows her decapitating Holofernes, in a “scene of horrific struggle and blood-letting.” She – Gentileschi – was raped earlier in life, which apparently wasn’t that unusual at the time. What was unusual was that she “participated in prosecuting the rapist.” For many years that incident overshadowed her achievements as an artist, and she was “regarded as a curiosity.” But today she is seen as “one of the most progressive and expressionist painters of her generation.”

* * * *

Turning to the other notes, an asterisk (“*”) in the main text indicates that a word or two of explanation will be made in these notes. For example, about “Psalm 51.*” On many Sundays the Revised Common Lectionary has two “tracks,” or two sets of Bible readings to choose from. (At the same time, usually the second – New Testament – reading and Gospel reading are the same for both Tracks, as for September 11, 2016.) On that note, the church I attend usually follows Track 1, but Psalm 51 – listed on “Track 2″ – is much easier and much more interesting to write about.

The image of Tertullian is courtesy of EarlyChurch.org.uk: Tertullian of Carthage (c. 160 – 225).

Re: “Draw an I and then cross it out.” The article adds this proviso, “As if to say ‘Help me, Lord, to abandon my self-centeredness and self-will.’”

The Bible readings for Holy Cross Day – on the “Satucket or Daily Office Reading” website – are: “AMPsalm 66; Numbers 21:4-9; John 3:11-17,” and “PM Psalm 118; Genesis 3:1-15; 1 Peter 3:17-22.”

The lower image is courtesy of Camino de Santiago – Wikipedia.

At the end of

At the end of  For example, in the picture at the top of the page, St. James is seen

For example, in the picture at the top of the page, St. James is seen

On that note, the “Central Pyrenees” – at left – look way too much like the Chilkoot &^%$ Trail…

On that note, the “Central Pyrenees” – at left – look way too much like the Chilkoot &^%$ Trail… Which meant that beginning on Sunday, August 21 – the day after our two canoes landed at

Which meant that beginning on Sunday, August 21 – the day after our two canoes landed at  By Thursday, August 11, “Judges” had moved to the story of

By Thursday, August 11, “Judges” had moved to the story of

* * * *

* * * *

Also today, we passed through Dawson Creek, B.C., about 3:00 this afternoon. It’s the southern end of the Alaska Highway, as shown at right. And on the way we “gained an hour.” Once we crossed into British Columbia, 3:00 p.m. magically became 2:00 p.m.

Also today, we passed through Dawson Creek, B.C., about 3:00 this afternoon. It’s the southern end of the Alaska Highway, as shown at right. And on the way we “gained an hour.” Once we crossed into British Columbia, 3:00 p.m. magically became 2:00 p.m.

For starters, this Sunday’s Gospel is

For starters, this Sunday’s Gospel is  Note also that this July 29 is the

Note also that this July 29 is the  Closer to home – chronologically – is the

Closer to home – chronologically – is the  To repeat: Mary Magdalene was both the first person to see Jesus after his resurrection – as shown at right – and the first person “to testify to the resurrection of Jesus.”

To repeat: Mary Magdalene was both the first person to see Jesus after his resurrection – as shown at right – and the first person “to testify to the resurrection of Jesus.”

Two points. One is that this passage is Luke’s version of the “

Two points. One is that this passage is Luke’s version of the “ (See

(See  (The post includes the cute

(The post includes the cute ,-The.jpg)

“

“ June 29 – I’m sitting here in the dining room of my aunt’s home, in

June 29 – I’m sitting here in the dining room of my aunt’s home, in  But first note the definition of

But first note the definition of  See also the 2014 post

See also the 2014 post

We have two major

We have two major  Which brings up the controversy that’s been going on for over 2,000 years.

Which brings up the controversy that’s been going on for over 2,000 years. In this debate, John represented the Old Way. (Resulting in the kind of “ending” illustrated at left.) Jesus – on the other hand – represents the New Way. “John is the climax of the Law… But anyone who has been born anew in the kingdom of God has something better than what John symbolizes.” That would be

In this debate, John represented the Old Way. (Resulting in the kind of “ending” illustrated at left.) Jesus – on the other hand – represents the New Way. “John is the climax of the Law… But anyone who has been born anew in the kingdom of God has something better than what John symbolizes.” That would be  Turning to the Feast for June 29: Last year’s

Turning to the Feast for June 29: Last year’s

In my case, yesterday I went to the high-school graduation of my “favorite grandson named Austin.” And among other things, such life-changes for other people – especially those important to you – can lead you to do some

In my case, yesterday I went to the high-school graduation of my “favorite grandson named Austin.” And among other things, such life-changes for other people – especially those important to you – can lead you to do some  Like the ones for June 1, 2016. That was the morning I set out on my most-recent jaunt into the Okefenokee Swamp. (As detailed in

Like the ones for June 1, 2016. That was the morning I set out on my most-recent jaunt into the Okefenokee Swamp. (As detailed in  Wikipedia noted the

Wikipedia noted the  Or – for that matter – your grandfather giving you $100 for a graduation gift, but then adding, “don’t blow it ‘playing poker with your idiot buddies!'”

Or – for that matter – your grandfather giving you $100 for a graduation gift, but then adding, “don’t blow it ‘playing poker with your idiot buddies!'”

That article was affiliated with “the UK’s only museum” dedicated to the D-Day Landings,” near the “Southsea Castle in Portsmouth,” England. It included the picture at right, of last year’s “Canopies Over Normandy (

That article was affiliated with “the UK’s only museum” dedicated to the D-Day Landings,” near the “Southsea Castle in Portsmouth,” England. It included the picture at right, of last year’s “Canopies Over Normandy ( Then came

Then came