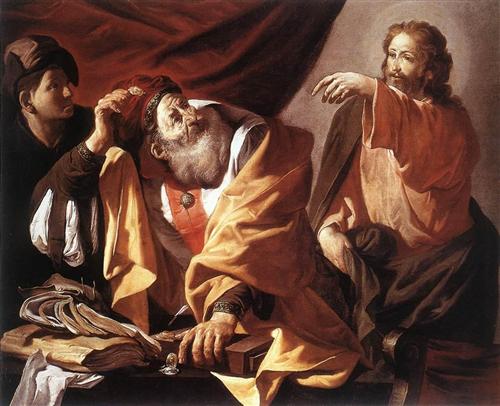

Saint Luke painting the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child…

* * * *

Today – Monday, October 19 – is the next major Feast Day.

It’s the Feast of St. Luke, who wrote the third-of-four Gospels. (Luke also wrote the Acts of the Apostles, “the fifth book of the New Testament.”)

Note also that the term “feast” as used here doesn’t refer to a large meal – as in a family celebration – but rather to an religious celebration dedicated to a particular saint.

I did a post last year, On St. Luke – physician, historian, artist. (Which included the painting at left, of St. Luke, by El Greco.)

I did a post last year, On St. Luke – physician, historian, artist. (Which included the painting at left, of St. Luke, by El Greco.)

For the Bible readings of the day, see St. Luke, Evangelist. They are Ecclesiasticus 38:1-4,6-10,12-14 – not to be confused with Ecclesiastes – along with Psalm 147, 2 Timothy 4:5-13, and Luke 4:14-21.

From the early days of the Church, Luke was described as a physician:

Eusebius (AD 260-340), considered to be the Father of Early Church History, described Luke the Physician in these terms: “Luke, who was by race an Antiochian and a physician by profession, was long a companion of Paul … and in two books left us examples of the medicine for the souls which he had gained from them.”

See Luke the Physician: with “Medicine for the Souls.” Thus the day’s Bible reading from Ecclesiasticus (also called The Wisdom of Sirach) begins appropriately like this: “Honor physicians for their services, for the Lord created them.” In turn, Psalm 147:3 speaks of God as the Ultimate Healer, with a side note that quite often He does His work using human hands. (By extension, His physicians: “He heals the brokenhearted and binds up their wounds. “)

As to the reading from the Second Letter to Timothy, Paul was in prison in Rome when he wrote it. He wrote that “the time of my departure has come” and that he had been deserted by those including Demas, Crescens and Titus. But note 2 Timothy 4:11, “Only Luke is with me.”

Luke was with St. Paul in his voyage to Rome (Acts 27:1; Acts 28:11, 16), and when he wrote the Epistles to the Colossians and Philemon [see Colossians 4:14], having doubtless composed the Acts of the Apostles during St. Paul’s two years’ imprisonment (Acts 28:30).

(See the Pulpit Commentary.) Which brings up what Garry Wills had to say about St. Luke.

In his book What the Gospels Meant, Wills noted that Luke wrote the longest Gospel, and that Acts of the Apostles is almost as long. He added that these two volumes “thus make up a quarter of the New Testament.” (And that they are longer than all 13 of Paul’s letters.)

He said Luke is considered the most humane of the Gospel writers. He quoted Dante – shown at right – as saying that Luke was a “describer of Christ’s kindness.” He added a quote from Ernest Renan , who referred to Luke’s Gospel “the most beautiful book that ever was.”

He said Luke is considered the most humane of the Gospel writers. He quoted Dante – shown at right – as saying that Luke was a “describer of Christ’s kindness.” He added a quote from Ernest Renan , who referred to Luke’s Gospel “the most beautiful book that ever was.”

And Wills added that Luke showed a “special sensitivity to women.” A notable example is Luke’s treatment of The Woman with the Menstrual Disorder. (From Chapter 8, “A Jesus for Outcasts.”) Here’s what Wills said about the episode, from Luke 8, verses 43-48:

Jesus’ embrace of the despised is made very clear in the case of [this] woman with a perpetual discharge… Each month when a Jewish woman underwent her period, she had to go to the Temple or the ritual baths to be purified. So the woman with a perpetual discharge was permanently unpurifiable. She was not only barred from the Temple but all her dealings with others would make them unclean. (E.A.)

Note that this sense of a woman being permanently unpurifiable was in keeping with Leviticus 15, verses 25-27: “When a woman has a discharge of blood for many days … she will be unclean as long as she has the discharge… Anyone who touches [her] will be unclean.” And this woman had suffered for 12 long years. And so finally now, “defying the ban on contact with others, she pushes through the crowd around Jesus and touches the tassels on His robe.”

Here she was – “permanently unclean” – and yet she had the audacity to approach Jesus.

Which is a reminder that sometimes it pays to be a bit pushy with God. (See also Arguing with God.) The other point is that Jesus – being Jesus – sensed what happened. In response the woman, “in a panic,” confessed her effrontery, and said she’d been instantly healed. But Jesus – being Jesus – said only, “Daughter, your faith has healed you. Go in peace.” (See Luke 8:48.)

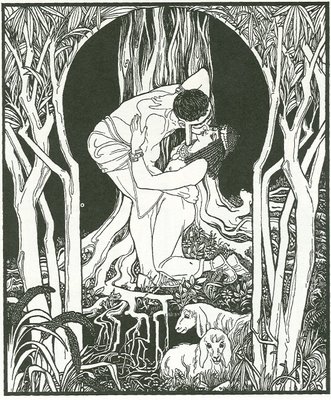

Then there’s the Parable of the Prodigal Son (illustrated at left). And as noted below, this lesson in God’s boundless love appears only in Luke:

Then there’s the Parable of the Prodigal Son (illustrated at left). And as noted below, this lesson in God’s boundless love appears only in Luke:

The richness of the parable comes from the fact that it can be read, as it were, backwards and forwards… It is an endlessly reversible tale of the Father’s bounty… Luke [] is at his very best in this parable that opens up endless mirrors of meaning… I think it would be fair to describe the tale of the Prodigal Son as containing the inmost kernel of Luke’s thinking and theology, according to which we are all outcasts, and Jesus is coming to rescue us all.

(Which brings up the tangential concepts of mashal, if not nimshal. For more, see the notes.)

But in closing, it should be added that to many scholars, “Luke is a historian of the first rank [and] should be placed along with the very greatest of historians.” Beyond that:

Only in Luke do we hear the story of the Prodigal Son welcomed back by the overjoyed father. Only in Luke do we hear the story of the forgiven woman disrupting the feast by washing Jesus’ feet with her tears. Throughout Luke’s gospel, Jesus takes the side of the sinner who wants to return to God’s mercy… Reading Luke’s gospel gives a good idea of his character as one who loved the poor, who wanted the door to God’s kingdom opened to all, who respected women, and who saw hope in God’s mercy for everyone.

For more see last year’s St. Luke – physician, historian, artist, with the Collect of the Day: “Almighty God, who inspired your servant Luke the physician to set forth in the Gospel the love and healing power of your Son: Graciously continue in your Church this love and power to heal…“

Saint Luke, by El Greco (circa 1607)…

Saint Luke, by El Greco (circa 1607)…

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of File: Maarten van Heemskerck – St Luke Painting the Virgin, and/or “Wikimedia.” See also Maarten van Heemskerck – Wikipedia, which noted that the artist (1498-1574) was a “Dutch portrait and religious painter, who spent most of his career in Haarlem,” and did the painting above in or about 1532.

Re: The actual “feast of St. Luke.” Normally it’s October 18, but according to The Lectionary Page, this year the date was transferred to the 19th, because the 18th fell on a Sunday. (For those interested in the reason for such transfers – or other such minutiae – see What happens when a saint’s feast falls on a Sunday?) On the other hand, some churches celebrated the feast day anyway, even though it fell on a Sunday. One example was St. John’s Episcopal Church Savannah GA. That’s where I went yesterday, during a weekend family visit to Savannah.

Of note: St. John’s offers traditional worship from the 1928 Book of Common Prayer. (Complete with all the “thees” and “thous” found in Elizabethan English. And including those “eths:” “And the third day he rose again according to the Scriptures: And ascended into heaven, And sitteth on the right hand of the Father.) That’s as opposed to the 1979 revision of the Book of Common Prayer used in most American Episcopal churches. Again, those interested in such minutiae can find more information at The 1928 U. S. Book of Common Prayer, and/or Book of Common Prayer – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Re: Paul writing “Second Timothy” while in prison. See 2 Timothy: About Paul’s second letter to Timothy. On the other hand, the Wikipedia article indicated that 2d Timothy was “not written by Paul but by an anonymous follower, after Paul’s death.”

Re: Garry Wills. Other posts or pages mentioning Wills include The True Test of Faith, On St. Mark’s “Cinderella story,” and On Peter, Paul – and other “relics.”

A side note: The quotes in What the Gospels Meant are from the 2009 Penguin Books edition, beginning at page 109-11, and – from Chapter 8 – pages 127, 132-33, and 136-40.

The lower image is courtesy of St. Luke of El Greco – Wikipedia, one of several interpretations by the artist. See for example last year’s On St. Luke, which included a painting shown courtesy of wikimedia.org/wiki/File: El_Greco_-_St_Luke_-_WGA10577.jpg, which included this note:

El Greco portrayed the apostles with a powerfully expressive body language. This St. Luke is from a cycle for the Toledo Cathedral… El Greco included St. Luke in several of his [paintings of the Apostles] although Luke was not actually one of the twelve apostles. Here the artist provided the Western version of a subject he depicted in quite different terms during his period as an icon painter.

* * * *

See also On three suitors, on interpreting such parables, “strictly” or otherwise. That post noted that quite often, in transposing a parable from oral to written form, it needed an interpretation added. The Hebrew word for such interpretation is nimshal, or the plural nimshalim:

The essence of the parabolic method of teaching is that life and the words that tell of life can mean more than one thing. Each hearer is different and therefore to each hearer a particular secret of the kingdom [of God] can be revealed. We are supposed to create nimshalim for ourselves.

St. Teresa was recently dubbed “

St. Teresa was recently dubbed “ More to the point,

More to the point,  In 1622 she was

In 1622 she was

That brings up the fact that last October 6 was the Feast Day for “

That brings up the fact that last October 6 was the Feast Day for “ One example: A witness testifies at trial that “Sally told me Tom was in town,” as opposed to being able to testify, “I saw Tom in town.” The question is: Which form of evidence is considered more reliable? To most people – and based on centuries of

One example: A witness testifies at trial that “Sally told me Tom was in town,” as opposed to being able to testify, “I saw Tom in town.” The question is: Which form of evidence is considered more reliable? To most people – and based on centuries of  And that of course includes the

And that of course includes the  “The title reflects [the] portrayal of More as the ultimate man of

“The title reflects [the] portrayal of More as the ultimate man of  Then there’s Psalm 127, one of the readings for Tuesday, October 6. Which leads to the fact that some people tend – in my view – to take isolated passages of the Bible way out of context. One example is people who “handle” snakes, based on .) (See

Then there’s Psalm 127, one of the readings for Tuesday, October 6. Which leads to the fact that some people tend – in my view – to take isolated passages of the Bible way out of context. One example is people who “handle” snakes, based on .) (See

,-The.jpg)

But most people don’t know that calling someone a “Samaritan” in the time of Jesus was pretty much like calling him a “

But most people don’t know that calling someone a “Samaritan” in the time of Jesus was pretty much like calling him a “ The story goes back to the time of

The story goes back to the time of

See

See  And the usual fate of heretics was to be massacred, as shown at left.

And the usual fate of heretics was to be massacred, as shown at left.

But the issue here is whether today’s Gospel tends to prove that Jesus was either a Conservative or a Liberal.

But the issue here is whether today’s Gospel tends to prove that Jesus was either a Conservative or a Liberal. In still further words, Jesus seemed to be showing that He was a true

In still further words, Jesus seemed to be showing that He was a true  But in the reading for September 27, Haman’s plans come unraveled. (As shown metaphorically at left.)

But in the reading for September 27, Haman’s plans come unraveled. (As shown metaphorically at left.)

But

But  Meanwhile, back to St. Matthew. (See

Meanwhile, back to St. Matthew. (See  Asimov noted that Matthew’s name came from the Hebrew meaning “gift of God,” and that it was a common name in New Testament times. This was due in large part to “the great pride of the Jews in the achievements of priest

Asimov noted that Matthew’s name came from the Hebrew meaning “gift of God,” and that it was a common name in New Testament times. This was due in large part to “the great pride of the Jews in the achievements of priest  Another interpretation of Jesus “calling” Matthew…

Another interpretation of Jesus “calling” Matthew…

The readings for August 15 – the day that my brother and I launched our canoe from

The readings for August 15 – the day that my brother and I launched our canoe from  The Gospel for August 17 featured Jesus

The Gospel for August 17 featured Jesus  The Gospel for August 27 was

The Gospel for August 27 was

I’m leaving town on Monday, August 10, and won’t be back until August 27. (A matter of some “unfinished business,”

I’m leaving town on Monday, August 10, and won’t be back until August 27. (A matter of some “unfinished business,”  Then for August 30 the OT reading changes again, from Kings to the “Song of Solomon” or

Then for August 30 the OT reading changes again, from Kings to the “Song of Solomon” or  The OT reading for August 23 –

The OT reading for August 23 –

Jesus, sharing the “Bread of Life” at Emmaus – as discussed in the Gospel for August 9…

Jesus, sharing the “Bread of Life” at Emmaus – as discussed in the Gospel for August 9…

But Absalom was eventually killed in battle, despite David’s orders that he not be harmed. The death of Absalom is shown at left, courtesy of

But Absalom was eventually killed in battle, despite David’s orders that he not be harmed. The death of Absalom is shown at left, courtesy of  The New Testament reading –

The New Testament reading –

Re: “all that you can be.” See

Re: “all that you can be.” See