Vince Lombardi on The basics: “Gentlemen, this is a football!”

* * * *

This is a reprise of a post I did back in April 2014: Some Bible basics from Vince Lombardi and Charlie Chan. It started a couple days ago when I went back to check some of the first posts I did for this blog. In this one, I saw that the images I’d put in were no longer there.

So, rather than fool around looking up new images for an old post, I figured I’d do what Jesus suggested in Mark 2:21-22:

So, rather than fool around looking up new images for an old post, I figured I’d do what Jesus suggested in Mark 2:21-22:

“No one sews a patch of unshrunk cloth on an old garment… And no one pours new wine into old wineskins…”

So this “new wineskin” will begin with Vince Lombardi – in the upper image – being a fanatic on teaching the basics of football. It starts with a story about Vince’s reaction to his Green Bay Packers losing to a team they should have beaten handily. (A loss where the team looked “more like whipped puppies.”) At practice the following Monday, Lombardi began by saying, “This morning, we go back to basics.”

Then – holding up an object for the team to see – Lombardi said, “Gentlemen, this is a football!”

So, here are some basics for understanding the Bible. And on how reading the Bible can help you become “all that you can be,” like the old Army commercial said.

For starters there’s the second part of John 6:37. That’s where Jesus made a promise to each one of us, for all time: “Anyone who comes to me, I will never turn away.” That’s a promise we can take to the bank, metaphorically and otherwise.

That is, we are aren’t “saved” by being members of a particular denomination. (No matter how much they may tell you to the contrary.) We are saved by starting that John 6:37 “walk toward Jesus.” We start the interactive process of walking down that road to knowing Him better.

And the best way to start that walk is by reading the Bible on a regular basis.

Unfortunately, many people start reading the Bible as if it were a novel. (Like one by Charles Dickens, seen at right.) They start at the very beginning and move toward the end. But they tend to bog down in Leviticus. (If they get that far.)

Unfortunately, many people start reading the Bible as if it were a novel. (Like one by Charles Dickens, seen at right.) They start at the very beginning and move toward the end. But they tend to bog down in Leviticus. (If they get that far.)

Jesus may have known the problem would come up, so He did us a favor. He boiled down the message of the entire Bible into two simple sentences. (A kind of “Cliff-Note” summary):

Hear what our Lord Jesus Christ said: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your strength, and with all your mind. This is the first and great commandment, and the second is like unto it: you shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets.”

That’s Matthew 22:37-39, where Jesus boiled the whole Bible down to two simple “shoulds.” You should try all your life to love, experience and get to know “God” with all you have. And to the extent possible, you should try to live peaceably with your “neighbors.”

In plain words, your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to become one with the “unified whole” that is our world today. (A big part of which is God, who started the whole thing…)

So, whenever you read something in the Bible that doesn’t make sense, or might mean two different things, or seems contrary to “common sense,” you have this Summary to fall back on. (It also works if you hear something from a slick televangelist that just doesn’t sound right.)

For example, some Christians become snake handlers. (Like “Stumpy,” at left.) They do this based on a literal interpretation of Mark 16:18. In other words, taking an isolated passage from the Bible out of context:

For example, some Christians become snake handlers. (Like “Stumpy,” at left.) They do this based on a literal interpretation of Mark 16:18. In other words, taking an isolated passage from the Bible out of context:

“In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues. They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.”

(But see also On snake-handling, Fundamentalism and suicide, Part I and Part II.)

Other Christians work to develop large families – as a way of showing their faith – again based on focusing literally on Psalm 127:3-5, taking that one passage out of context: “Children are a gift from God; they are his reward. Children born to a young man are like sharp arrows to defend him. Happy is the man who has his quiver full of them.” (See Quiverfull – Wikipedia.)

On the other hand, you could approach the Bible as presenting a plain, common-sense view of some people in the past who have achieved that “union with a Higher Power.” (Which is of course the goal of most religions and/or other spiritual or ethical disciplines.)

So what’s the pay-off?

Simply put, the discipline of regular Bible-reading can lead to a capacity to transcend the painful and negative aspects of life. It can also lead to the ability to live with “serenity and inner peace.” On the other hand, the discipline could also lead to a your developing a “zest, a fervor and gusto in life plus a much higher ability to function.”

To some people, that flies in the face of the popular view of “Christians.” (Some of whom seem to revel more in telling others how they should live their lives.) Which leads to the question: “Do you have to be grumpy to be a Christian?” The answer is: “Probably not.”

For example, someone asked Thomas Merton (American Trappist Monk) this question: “How can you tell if a person has gone through inner, spiritual transformation?” Merton smiled and said, “Well it is very difficult to tell but holiness is usually accompanied by a wonderful sense of humor…”

For example, someone asked Thomas Merton (American Trappist Monk) this question: “How can you tell if a person has gone through inner, spiritual transformation?” Merton smiled and said, “Well it is very difficult to tell but holiness is usually accompanied by a wonderful sense of humor…”

Then too, Jesus Himself said, “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly.” (See the second part of John 10:10, in the RSV, emphasis added. Or as translated in The Living Bible (Paraphrased): “My purpose is to give life in all its fullness.”) So what’s not to be happy about?

Which means that ideally, one who reads the Bible on a daily basis should not become an intolerant, self-righteous prig. (Going around telling others how to live.) Or as Saint Peter said, “Don’t let me hear of your … being a busybody and prying into other people’s affairs.” (See 1st Peter 4:15, in The Living Bible translation. And note that in most other translations, “meddlers” and “busybodies” are ranked right up there with murderers, thieves and evil-doers.)

Instead, such Bible-Reading on a regular basis should lead to a well-adjusted and open-minded person. And also one who is tolerant of the inherent weaknesses – including his own – of all people. In other, a person able to live life “in all its fullness.”

So how do you do all that?

One of the best ways to begin may be from one of the great philosophers of our time:

* * * *

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of PACKERVILLE, U.S.A.: “Gentlemen, this is a football.”

The wineskin image is courtesy of firesetternews.blogspot.com/2012/09/wineskins.

The Charles Dickens image is courtesy of English novel – Wikipedia. See also Reading a Novel Boosts Brain Connectivity – PsyBlog. As to reading novels:

“A great book should leave you with many experiences, and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading.”

Hey, I’m convinced! But it’s still not a good way to read the Bible. The better way – I suggest – is to do the Daily Office. (See also What’s a DOR?) The daily blending of four short readings – Psalm, Old Testament, New Testament and Gospel – tends to help keep you from getting bogged down.

Re: “Leviticus.” See What’s the Most Boring Book in the Bible? | Fr. Anthony Messeh: “No doubt about it. To me, Leviticus is by far the hardest book in the Bible to read. It is (forgive me again God) filled with boring detail after boring detail – things that seem to have no bearing on my life today.”

Or just Google “leviticus boring.”

Re: “your mission, should you choose to accept it.” (Wiktionary.) See also Your Mission, Should You Choose To Accept It…. – YouTube.

Re: Quiverfull. See also What You Need To Know About The ‘Quiverfull’ Movement, and/or What Is Quiverfull? – Patheos. Or just Google the term…

The quotes about “capacity to transcend,” “serenity and inner peace,” and “zest, a fervor and gusto in life” are from How to Meditate: A Guide to Self-Discovery, by Lawrence LeShan. See also On the Bible as “transcendent” meditation:

Lawrence LeShan’s book How to Meditate (1974), “one of the first practical guides to meditation.” As I recall, my first copy cost under $2.00. (And incidentally, LeShan noted that “anyone who gives (or sells) you a mantra designed just for you … is pulling your leg.”)

The Thomas Merton image is courtesy of Why are so Many Believers so Dour? | joy of nine9. See also my post from July 2014, On Thomas Merton, and Thomas Merton – Wikipedia.

The lower image is courtesy of Charlie Chan Mind Like Parachute Image Results. See also Charlie Chan (Wikipedia). The quote is said to have come from Charlie Chan at the Circus, and in the form given. See Charlie Chan – Wikiquote and Reel Life Wisdom – The Top 10 Wisest Quotes from Charlie Chan. But I could have sworn that the actual quote was, “Mind like parachute; work best when open.”

* * * *

Other sources on Vince Lombari included Greatest Coaches in NFL History – Vince Lombardi – ESPN.com, Vince Lombardi – Coach – Biography.com, Vince Lombardi – Wikipedia, Vince Lombardi | Home, and Vince Lombardi Isn’t Who You Think He Is | VICE Sports.

We left off – at the end of “

We left off – at the end of “ Your third step is to realize how much counseling is available.

Your third step is to realize how much counseling is available. (And if all that isn’t enough to get you reading the Bible on a regular basis, consider the post by Mike Mooney,

(And if all that isn’t enough to get you reading the Bible on a regular basis, consider the post by Mike Mooney,

That is, you begin the

That is, you begin the  That is, the interactive process of walking toward Jesus is much like that “1985

That is, the interactive process of walking toward Jesus is much like that “1985  And as explained below, when you accept JCPD, you get put on a kind of “

And as explained below, when you accept JCPD, you get put on a kind of “ On that note, consider the story Sam Ervin – at right – once told of an old North Carolina lawyer. The old lawyer was asked how he could justify arguing for a client he knew was guilty:

On that note, consider the story Sam Ervin – at right – once told of an old North Carolina lawyer. The old lawyer was asked how he could justify arguing for a client he knew was guilty:

The lower image is courtesy of

The lower image is courtesy of

Deuteronomy 29:2-15 is part of “concluding discourse” of Moses, on renewing the covenant between God and the Hebrews. See

Deuteronomy 29:2-15 is part of “concluding discourse” of Moses, on renewing the covenant between God and the Hebrews. See  The Gospel – Luke 18:15-30 – began with people bringing children for Jesus to bless. The disciples tried to stop it, but:

The Gospel – Luke 18:15-30 – began with people bringing children for Jesus to bless. The disciples tried to stop it, but: Personally I think it’s the “rote answer.”

Personally I think it’s the “rote answer.” In other words, this June 6th calls for us to remember the sacrifices of those brave members of the armed services 71 years ago, as part of the Allied invasion of Normandy.

In other words, this June 6th calls for us to remember the sacrifices of those brave members of the armed services 71 years ago, as part of the Allied invasion of Normandy.

But as we all know, life doesn’t work that way. No one has found the magic formula to change God into a “magic genie” who will cater to our every whim. (See

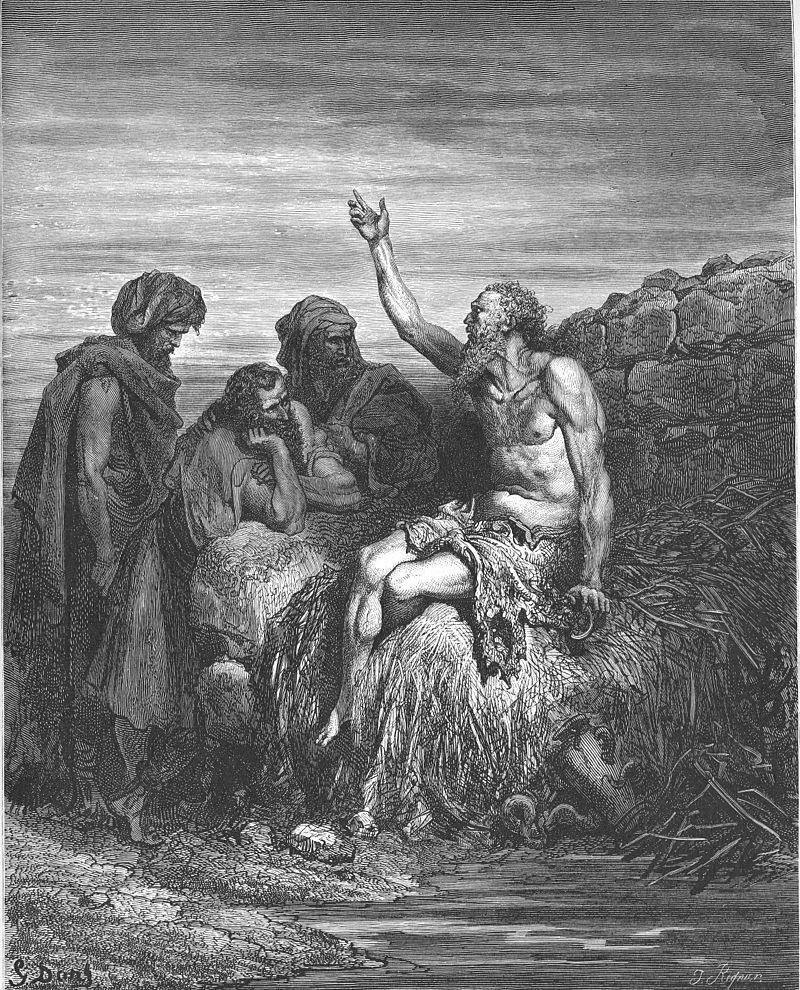

But as we all know, life doesn’t work that way. No one has found the magic formula to change God into a “magic genie” who will cater to our every whim. (See  “Job and his friends…”

“Job and his friends…”