“The actor Roger Rees renders [William] Bradford beautifully,” in Ric Burns’ “The Pilgrims…”

* * * *

[Editor’s note: I originally posted this under the title, “A review of Ric Burns’ ‘Pilgrims’ DVD.” I’ll be writing a review and re-write of this post some time near January 2021, with the tentative title, “Two years ago today.”]

To preview what’s coming up in the Church Calendar for 2019 – including a continuation of the Season of Epiphany – see Happy Epiphany – 2018. Among the Feast Days coming up are the Confession of St Peter, Apostle, on January 18; the Conversion of St Paul, Apostle, on January 25; and the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, on February 2.

That all leads to the Last Sunday after the Epiphany, March 3, and that takes us to the beginning of Lent. And Lent – a season of “penance, mortifying the flesh, repentance of sins, almsgiving, and self-denial” – begins with Ash Wednesday, symbolized at right. This year it falls on March 6.

That all leads to the Last Sunday after the Epiphany, March 3, and that takes us to the beginning of Lent. And Lent – a season of “penance, mortifying the flesh, repentance of sins, almsgiving, and self-denial” – begins with Ash Wednesday, symbolized at right. This year it falls on March 6.

Meaning Easter Sunday will be pretty late this year, on April 21.

“In the meantime,” again, I offer this review of a DVD I just finished watching: American Experience: The Pilgrims, a documentary film by Ric Burns. (Available at Amazon.com.)

I must say that – overall – I found the tone pretty depressing. I wrote before – in Thanksgiving 2015 for example – that of the 102 Pilgrims who landed in November 1620 at Plymouth Rock, less than half survived the first year. (To November 1621.) And of the 18 adult women, only four survived that first winter in the hoped-for “New World.” (Illustrated at left.)

I must say that – overall – I found the tone pretty depressing. I wrote before – in Thanksgiving 2015 for example – that of the 102 Pilgrims who landed in November 1620 at Plymouth Rock, less than half survived the first year. (To November 1621.) And of the 18 adult women, only four survived that first winter in the hoped-for “New World.” (Illustrated at left.)

I just hadn’t appreciated the extent of that loss on an emotional level. Another way of saying that – just as at Jamestown, started in 1607 – there was a whole lot of human suffering:

The major similarity between the first Jamestown settlers and the first Plymouth settlers was great human suffering… November was too late to plant crops. Many settlers died of scurvy and malnutrition during that horrible first winter. Of the 102 original Mayflower passengers, only 44 survived. Again like in Jamestown, the kindness of the local Native Americans saved them from a frosty death.

In Thanksgiving – 2016, I wrote that the “men and women who first settled America paid a high price, so that we could enjoy the privilege of stuffing ourselves into a state of stupor.” But the Ric Burns film brought that suffering home in a way I hadn’t fully appreciated before.

And by the way, the full caption for the picture at the top of the page reads, “The actor Roger Rees renders Bradford beautifully; it was among his last performances before his death in July,” 2015. Which could be both prescient and ironic. That is, while Rees died at 71 – when life expectancy today is about 78 – William Bradford lived to the ripe old age of 67, when life expectancy was about half that.

And by the way, the full caption for the picture at the top of the page reads, “The actor Roger Rees renders Bradford beautifully; it was among his last performances before his death in July,” 2015. Which could be both prescient and ironic. That is, while Rees died at 71 – when life expectancy today is about 78 – William Bradford lived to the ripe old age of 67, when life expectancy was about half that.

There’s more about that at the end of this post…

But what I found most fascinating was how Bradford’s journal, Of Plymouth Plantation, proved the truth of the old adage, “Everything perishes, save the written word.*” For starters, here’s what Wikipedia said about Plymouth Colony in general:

Despite the colony’s relatively short existence, Plymouth holds a special role in American history… The events surrounding the founding and history of Plymouth Colony have had a lasting effect on the art, traditions, mythology, and politics of the United States of America, despite its short history of fewer than 72 years.

And what gave “Plymouth” such a special place in American history? Bradford’s journal, Of Plymouth Plantation. (Which proves again, “Everything perishes, save the written word.”) And which brings up another thing that I hadn’t realized: That the book was almost lost to history.

That is, the original manuscript was left in the tower of the Old South Meeting House in Boston during the American Revolution. But after British troops occupied Boston, it disappeared “for the next century.” The missing manuscript was finally re-discovered, “in the Bishop of London‘s library at Fulham Palace,” and printed again in 1856. It was only after much finagling – including a verdict ultimately rendered by the Consistorial and Episcopal Court of London – that the manuscript was brought back to the U.S. and given to Massachusetts in 1897.

That’s one of several points noted by the New York Times’ In ‘The Pilgrims,’ Ric Burns Looks at Mythmaking. (Including the Plymouth “Signing of the Mayflower Compact.”)

That’s one of several points noted by the New York Times’ In ‘The Pilgrims,’ Ric Burns Looks at Mythmaking. (Including the Plymouth “Signing of the Mayflower Compact.”)

Mr. Burns’s most inspired touch is to end not in the 1600s, but two centuries later, by following what happened to Bradford’s journal. It disappeared during the Revolutionary War, then was rediscovered in the mid-1800s… The Mayflower passengers suffered terrible hardships, and from the Indians’ point of view their arrival was ultimately a dark day. But not on Thanksgiving. “There’s been a tremendous amount of memory produced around the Pilgrims, but there’s also been a lot of forgetting,” the literary critic Kathleen Donegan notes, adding later: “We don’t think about the loss. We think about the abundance.”

Or consider this, from Who Were the Pilgrims Who Celebrated the First Thanksgiving. “The first winter, people died from dysentery, pneumonia, tuberculosis, scurvy, and exposure, at rates as high as two or three per day. ‘It pleased God to visit us then with death daily,’ Bradford wrote.”

But the Pilgrims were “inventive enough” to conceal their losses from the Indians: “inventive enough, as Donegan notes, to prop up sick men against trees outside the settlement, with muskets beside them, as decoys to look like sentinels to the Indians.”

The point is this: Our “Forefathers” – and Foremothers as well – suffered greatly to come to America, and usually much more than we appreciate. More than that, from the beginning they were “aliens in a strange land.” Which brings up Deuteronomy 10:19, where God said to the Children of Israel: “You are also to love the resident alien, since you were resident aliens in the land of Egypt.” And that’s a point worth remembering these days…

But let’s close with a note of hope and cheer, at least for me. That is, rumor has it that William Bradford was one of my long-ago ancestors. If that’s true, I hope I inherited his longevity gene.

That earlier “Bradford” lived to a ripe old age of 67. That was at a time when life expectancy for that time and place was about half that long. See for example, life expectancy in America in the years 1750-1800. That is, the life expectancy a century after Bradford’s time – he died in 1657 – was 36 years. So if that “1.86 factor” applied to me today – with a male U.S. life expectancy of 76 years – I should live to be 141. (Giving me another 74 years.)

And who knows, I might end my years with the old-age benefits of King David:

King David was old and advanced in years; and although they covered him with clothes, he could not get warm. So his servants said to him, ‘Let a young virgin be sought for my lord the king, and let her wait on the king, and be his attendant; let her lie in your bosom, so that my lord the king may be warm.’ So they searched for a beautiful girl throughout all the territory of Israel, and found Abishag the Shunammite, and brought her to the king. The girl was very beautiful. She became the king’s attendant and served him, but the king did not know her…

(In the biblical sense.) On the other hand, King David didn’t have all the “better living through chemistry” advantages we have today. And that will no doubt increase by, say, 2080?

Something to look forward to…

* * * *

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of Review (NYT): In ‘The Pilgrims,’ Ric Burns Looks at Mythmaking.

Re: “Everything perishes save the written word.” The quote is from Techniques of Fiction Writing: Measure and Madness, by

But –

Through measure a story is given the structure and style that snatch it from the chaos of reality and fix it in the memory of man. We remember through measure. We move from the unrealized to the realized through measure. Through measure writing resists the ravages of time. Everything perishes save the written word, says an old eastern proverb.

From the 1969 Anchor Books paperback edition, at pages 242-44, emphasis added.

The image to the right of the paragraph ending, “Bradford lived to the ripe old age of 67, when life expectancy was about half that,” shows the “Coat of Arms of William Bradford.”

Also from (New York Times) Review: In ‘The Pilgrims,’ Ric Burns Looks at Mythmaking:

The Pilgrims and their fellow travelers weren’t terrorists, of course (despite an instance of putting the severed head of a perceived enemy on a pole), but they and those who followed certainly did effect a cultural conquest. Some versions of their story play that down, partly because a plague resulting from earlier contact with Westerners brought widespread death to coastal Indians in the Northeast just before the Mayflower arrived. God, it seemed to some, killed off the Indians to make way for the whites, a view this program corrects.

Here’s more from Who Were the Pilgrims Who Celebrated the First Thanksgiving:

It draws on the unique, nearly lost history, Of Plymouth Plantation, written by William Bradford, the new colony’s governor for more than 30 years, whom the late actor Roger Rees portrays from a script derived from Bradford’s book.

Right from the start, the death rate was awful. Mortality had been enormous at the Jamestown colony, where by 1620 nearly 8,000 people had arrived, although the settlement was struggling to keep its population above a thousand. Bradford’s history recalled the Pilgrims’ anticipation of “a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men.” Ferrying in supplies from the ship meant wading through ice-cold water, at one point with sleet glazing their bodies with ice. The first winter, people died from dysentery, pneumonia, tuberculosis, scurvy, and exposure, at rates as high as two or three per day. “It pleased God to visit us then with death daily,” Bradford wrote…

See also PBS Documentary “The Pilgrims”: A Review.

The lower image is courtesy of King David Abishag – Image Results. The painting may actually show Bathsheba, see Moritz Stifter Bathsheba – Image Results, and/or Bathsheba Painting – Image Results. The “Abishag” connection was gleaned from “Interesting Green: Reflection – King David and Abishag,” from veryfatoldmanblogspot.com. But see also Is Veryfatoldman.blogspot legit and safe? (Review).

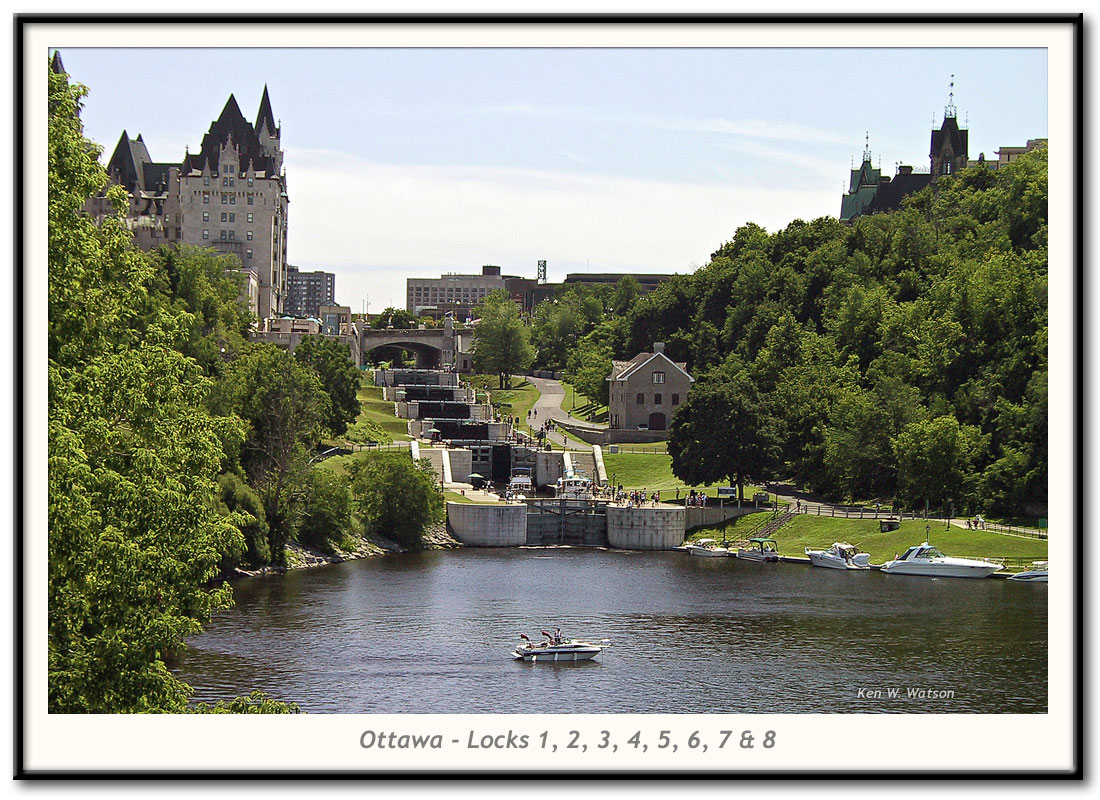

I just got back from three weeks canoeing the

I just got back from three weeks canoeing the

So the “40 days of Lent” are supposed to commemorate the 40 days that Jesus spent “wandering in the wilderness.” (And being “tempted.”) In turn, that act by Jesus mirrored the 40 years that the Hebrews – led by Moses – also spent “wandering around.” But as it’s evolved, most people today equate Lent with “giving up something they love.” Which may miss the point entirely. (See e.g.,

So the “40 days of Lent” are supposed to commemorate the 40 days that Jesus spent “wandering in the wilderness.” (And being “tempted.”) In turn, that act by Jesus mirrored the 40 years that the Hebrews – led by Moses – also spent “wandering around.” But as it’s evolved, most people today equate Lent with “giving up something they love.” Which may miss the point entirely. (See e.g.,  Which turned out to be pretty

Which turned out to be pretty

.jpg)

Well, we did it. My brother and I arrived in

Well, we did it. My brother and I arrived in

Re: “Different kind of hell.” The allusion is to

Re: “Different kind of hell.” The allusion is to

In less than 24 hours I’ll be winging my way from Atlanta to

In less than 24 hours I’ll be winging my way from Atlanta to  And one of the best-known pilgrimages involves the

And one of the best-known pilgrimages involves the  That is,

That is,  In other words, exploring the mystical side of the Bible helps you “be all that you can be.” See

In other words, exploring the mystical side of the Bible helps you “be all that you can be.” See  At the end of

At the end of  For example, in the picture at the top of the page, St. James is seen

For example, in the picture at the top of the page, St. James is seen

On that note, the “Central Pyrenees” – at left – look way too much like the Chilkoot &^%$ Trail…

On that note, the “Central Pyrenees” – at left – look way too much like the Chilkoot &^%$ Trail… Sunday, August 28 – I said this a year ago, but once again “

Sunday, August 28 – I said this a year ago, but once again “ Which meant that beginning on Sunday, August 21 – the day after our two canoes landed at

Which meant that beginning on Sunday, August 21 – the day after our two canoes landed at  By Thursday, August 11, “Judges” had moved to the story of

By Thursday, August 11, “Judges” had moved to the story of

In my case, yesterday I went to the high-school graduation of my “favorite grandson named Austin.” And among other things, such life-changes for other people – especially those important to you – can lead you to do some

In my case, yesterday I went to the high-school graduation of my “favorite grandson named Austin.” And among other things, such life-changes for other people – especially those important to you – can lead you to do some  Like the ones for June 1, 2016. That was the morning I set out on my most-recent jaunt into the Okefenokee Swamp. (As detailed in

Like the ones for June 1, 2016. That was the morning I set out on my most-recent jaunt into the Okefenokee Swamp. (As detailed in  Wikipedia noted the

Wikipedia noted the  Or – for that matter – your grandfather giving you $100 for a graduation gift, but then adding, “don’t blow it ‘playing poker with your idiot buddies!'”

Or – for that matter – your grandfather giving you $100 for a graduation gift, but then adding, “don’t blow it ‘playing poker with your idiot buddies!'” “Salome receives the Head of John the Baptist…”

“Salome receives the Head of John the Baptist…”

I did pack – in my spandy-new 2015 Ford Escape – an 8-foot kayak, along with a stair-stepping stand and a 22-pound weight vest. (To earn my

I did pack – in my spandy-new 2015 Ford Escape – an 8-foot kayak, along with a stair-stepping stand and a 22-pound weight vest. (To earn my  I did need to stop from time to time at local libraries, to use their computers. But that was only if I needed a secure connection, like to check my bank accounts or – with the Ford being so new – to make the first payment, a few days into the trip. (At the

I did need to stop from time to time at local libraries, to use their computers. But that was only if I needed a secure connection, like to check my bank accounts or – with the Ford being so new – to make the first payment, a few days into the trip. (At the  In this way my trip emulated Steinbeck’s visit to

In this way my trip emulated Steinbeck’s visit to  David and his

David and his

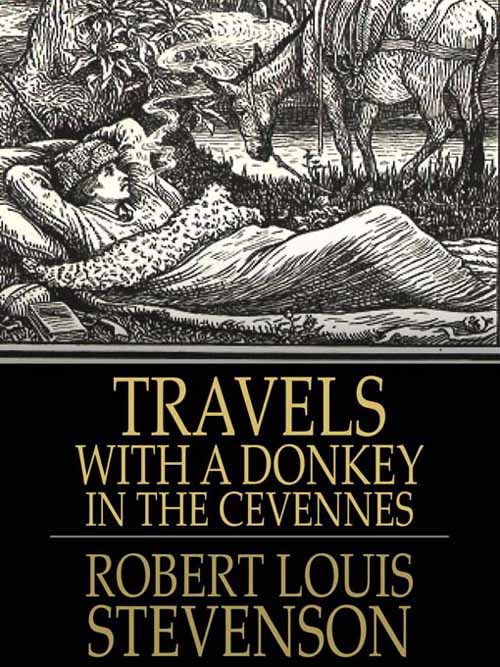

Which brings up some things Robert Louis Stevenson – shown at right – said in his

Which brings up some things Robert Louis Stevenson – shown at right – said in his